- Guided Tours

- Self Guide Smartphone Tour

-

Revere Bells Index

- The Stickney Revere Bell Listings of 1976

- Ashby Mass. Revere Bell

- Paul Revere Bell of Beverly

- Revere Bells in Boston >

- California's 2 Paul Revere Bells

- Paul Revere & Son's Bell Westborough Massachusetts

- Falmouth, Massachusetts

- Revere Bell Fredericksburg VA

- Revere Bell Hampton NH

- First Parish Church of Kennebunk

- Revere Bells in Maine

- Revere Bell in Mansfield

- Revere Bell of Michigan

- Revere Salem Mass Bell

- Roxbury First Unitariarn Universalist Church and their Revere Bell

- Revere & Son Bell, Savannah Georgia

- Singapore Revere Bell

- Tuscaloosa Bell >

- Revere Bells Lost in Time

- Revere Bells Washington DC

- Revere Bell in Wakefield, Mass

- Revere Bells Woodstock VT

-

Bostonians

- Edward F Alexander of The Harvard 20th Civil War Regiment

- Polly Baker

- John Wilkes Booth

- The Mad Hatter, Thomas, Boston Corbett who Killed John Wilkes Booth

- Richard-Henry-Dana-Jr

- James Franklin

- Benjamin Harris of Publick Occurrences

- Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr.

- William Lloyd Garrison

- USS Thomas Hudner DDG116

- Edward Hutchinson Robbins Revere

- Amos Lincoln

- King Philip

- Mayor's of Boston

- Mum Bett & Theodore Sedgwick

- James Otis

- Paul Joseph Revere

- Reverend Larkin's Horse

- John Rowe >

- Be Proud to be Called a Lucy Stoner

- Rachel Wall , Pirate

- Paul Revere the Coroner of Boston

- Deborah Sampson

- Who was Mrs. Silence Dogood?

- Dr. Joseph Warren's Dedication

- History Blog

- Lilja's of Natick

-

Collage of Boston

- 4th of July Parade, Bristol RI

- Boston Harbor

- The Customs House

- Forest Hills Cemetery

- Georges Island

- Nonviolent Monument to Peace - Sherborn

- The Battle Road

- Skate bike and scooter park

- Cassin Young & USS Cassin Young

- MIT

- Historic Charles River

- The Roxbury Standpipe on Fort Hill

- John & Abigail Adams National Park

- Boston's Racial History - Ante-Bellum

- New Page

Deborah Sampson descended from the Pilgrims of Plympton (sic), Massachusetts. She was born on December 17, 1760 , in Sharon Massachusetts, a community thirty-five miles south of Boston and forty-two miles southeast of Worcester. Sharon was hardly the center of patriotism or radical politics. Deborah was the oldest of six children from a poor family. Her father deserted the family. Literally, he sailed away. Her mother could not provide for them, and the Town of Sharon's safety net could not accommodate the seven Sampsons. Deborah was indentured at the early age of ten to a neighbor on a nearby farm. It was a hard life, but she learned to sew, hunt, ride, and modest woodworking. The adopted family all helped educate her. Deborah's indenture ended at eighteen, a little early to be set free from indenture terms. Her future employment as a school teacher and weaver must have given her a taste of independence.

In 1782 Deborah failed at volunteering for the Continental Army. She marched to Worcester dressed as a man hoping she would not be discovered. Her second attempt under the enlisted name of Robert Shurtliff found her quickly engaged with a Worcester regiment in the Hudson Valley, near West Point. She did some solo scouting on behalf of George Washington and led a successful raiding party.

In two years of service, Robert was wounded twice, but she managed to conceal her gender while being treated. She recovered from a sword wound to the head. She removed a bullet wound to her thigh by herself.[i] Typical of camp life, diseases were as much a concern as wounds. She developed a serious fever landing her in a Philadelphia hospital. Her doctor discovered her true gender.

Unfortunately, George Washington did not like any women in the camp do to the impact they had on discipline and the necessary extra support, food and baggage. He instructed his generals to remove all women from service to improve discipline. He handed Deborah her honorable discharge in writing but did not utter a word of thanks.

Benjamin Gannet of Sharon married Deborah on her return to Massachusetts. Deborah wrote her memoirs and toured New England in her military dress uniform and demonstrated battlefield techniques. The statue above, in front of the Sharon Library, merges her military clothing with her civilian attire. The Gannets suffered financial difficulties and applied for Deborah’s military pension. Congress rejected her request.

One day, twenty-one years later, Paul Revere visited the Town of Sharon. It was next to the Town of Canton, the home of Paul’s new foundry and forge. Paul took up her cause, writing to the Congressman for her district. In his words, Paul said, Deborah was “much more deserving than hundreds to whom Congress have been generous.” Paul Revere was qualified to make the above statement since he had three major military assignments. The Penobscot Expedition was a significant failure leading to court-martial charges against all officers, including him. He served with the Massachusetts militia, on Castle William, many months as a colonel and was part of the expedition to Rhode Island that failed to engage the enemy.

Revere rarely showed emotions in his various writings, except in the case of Deborah Sampson. He embedded his personality and his professional experience as he proselytized to Congress for her military pension. He was greatly satisfied with his efforts at achieving a veteran’s pension for her service. In total, twenty-one years of effort by the Gannets invigorated by Paul Revere's letter earned Deborah a pension of $4.00/month, equal to about $104 today.

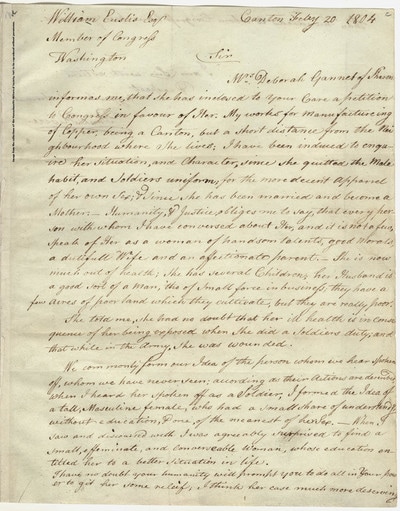

Below is a heartfelt letter by Paul Revere to Congressman William Eustis, dated February 20, 1804, in support of Deborah’s application for a pension. Paul’s next to the last paragraph may sound a bit peculiar today, but consider that he wrote it in the early part of the Nineteenth Century. Try your best not to judge him from the Twenty-first Century.

Deborah Sampson Gannett, like Paul Revere, is another of our early American heroes that deserve more attention.

Post Script

Four years after Deborah’s death, Benjamin Gannet applied for a survivor's pension petitioning directly to the United States Congress. Though they were not married at the time of her service, Congress concluded that there were no similar situations, and awarded the "survivors pension". Unfortunately, Benjamin died before Congress issued the payment.

There does seem to be some contradiction to the granting of Deborah’s honorable discharge. In contradiction, General Henry Knox or George Washington are credited. Washington may well have been too busy, but women in the camp were one of his many significant concerns.

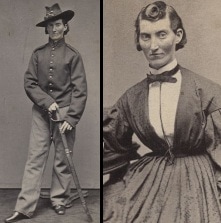

Was Deborah Sampson a model for women of the second revolution?(iv) It is estimated that between 400-700 women served clandestinely on both sides of the Civil War. For example, immediately below is Frances Clayton alias Frances Clalin of the Union Army.iii

Paul Revere would have endorsed the Commonwealth of Massachusetts designation of Deborah Sampson as the official state heroine on “Deborah Sampson Day,” May 23, 1982.

If you have further interest in Civil War women, Maggie Maclean’s “Civil War Women” referenced below is a very interesting read.

Bibliography

Mann, Herman. The Female Review: Life of Deborah Sampson, the Female Soldier in the War of Revolution. New York: Arno Press, 1972

http://www.masshist.org/database/viewer.php?item_id=326&img_step=1&mode=transcript#page1

"MHS Collections Online: Letter from Paul Revere to William Eustis, 20 February 1804." MHS Collections Online: Letter from Paul Revere to William Eustis, 20 February 1804. N.p., n.d. Web. 07 Mar. 2017.

National Women's History Museum." Education & Resources - National Women's History Museum – NWHM

Smith, Sam. "Female Soldiers in the Civil War." Civil War Trust. Civil War Trust, n.d. Web. 07 Mar. 2017.

MacLean, Maggie. "Maggie MacLean." Civil War Women. N.p., 23 Aug. 2015. Web. 07 Mar. 2017.

MassHist.org Paul Revere and Deborah Sampson, http://www.masshist.org/database/viewer.php?item_id=326&mode=dual&img_step=1&pid=3&nodesc=1&br=1#page1

Field Guide to U. S. Public Monuments & Memorials http://www.monumentsandmemorials.com/report.php?id=1041

End Notes

[i] "National Women's History Museum." Education & Resources - National Women's History Museum - NWHM. N.p., 05 Feb. 2010. Web. 07 Mar. 2017.

[ii] Library of Congress

iii MacLean, Maggie. "Maggie MacLean." Civil War Women. N.p., 23 Aug. 2015. Web. 07 Mar. 2017.

iv) Second revolution. A term often used by abolitionists to suggest the Civil War would correct some of the failings in the U. S. Constitution, such as its quiet endorsement of slavery.

- Guided Tours

- Self Guide Smartphone Tour

-

Revere Bells Index

- The Stickney Revere Bell Listings of 1976

- Ashby Mass. Revere Bell

- Paul Revere Bell of Beverly

- Revere Bells in Boston >

- California's 2 Paul Revere Bells

- Paul Revere & Son's Bell Westborough Massachusetts

- Falmouth, Massachusetts

- Revere Bell Fredericksburg VA

- Revere Bell Hampton NH

- First Parish Church of Kennebunk

- Revere Bells in Maine

- Revere Bell in Mansfield

- Revere Bell of Michigan

- Revere Salem Mass Bell

- Roxbury First Unitariarn Universalist Church and their Revere Bell

- Revere & Son Bell, Savannah Georgia

- Singapore Revere Bell

- Tuscaloosa Bell >

- Revere Bells Lost in Time

- Revere Bells Washington DC

- Revere Bell in Wakefield, Mass

- Revere Bells Woodstock VT

-

Bostonians

- Edward F Alexander of The Harvard 20th Civil War Regiment

- Polly Baker

- John Wilkes Booth

- The Mad Hatter, Thomas, Boston Corbett who Killed John Wilkes Booth

- Richard-Henry-Dana-Jr

- James Franklin

- Benjamin Harris of Publick Occurrences

- Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr.

- William Lloyd Garrison

- USS Thomas Hudner DDG116

- Edward Hutchinson Robbins Revere

- Amos Lincoln

- King Philip

- Mayor's of Boston

- Mum Bett & Theodore Sedgwick

- James Otis

- Paul Joseph Revere

- Reverend Larkin's Horse

- John Rowe >

- Be Proud to be Called a Lucy Stoner

- Rachel Wall , Pirate

- Paul Revere the Coroner of Boston

- Deborah Sampson

- Who was Mrs. Silence Dogood?

- Dr. Joseph Warren's Dedication

- History Blog

- Lilja's of Natick

-

Collage of Boston

- 4th of July Parade, Bristol RI

- Boston Harbor

- The Customs House

- Forest Hills Cemetery

- Georges Island

- Nonviolent Monument to Peace - Sherborn

- The Battle Road

- Skate bike and scooter park

- Cassin Young & USS Cassin Young

- MIT

- Historic Charles River

- The Roxbury Standpipe on Fort Hill

- John & Abigail Adams National Park

- Boston's Racial History - Ante-Bellum

- New Page