- Guided Tours

- Self Guide Smartphone Tour

-

Revere Bells Index

- The Stickney Revere Bell Listings of 1976

- Ashby Mass. Revere Bell

- Paul Revere Bell of Beverly

- Revere Bells in Boston >

- California's 2 Paul Revere Bells

- Paul Revere & Son's Bell Westborough Massachusetts

- Falmouth, Massachusetts

- Revere Bell Fredericksburg VA

- Revere Bell Hampton NH

- First Parish Church of Kennebunk

- Revere Bells in Maine

- Revere Bell in Mansfield

- Revere Bell of Michigan

- Revere Salem Mass Bell

- Roxbury First Unitariarn Universalist Church and their Revere Bell

- Revere & Son Bell, Savannah Georgia

- Singapore Revere Bell

- Tuscaloosa Bell >

- Revere Bells Lost in Time

- Revere Bells Washington DC

- Revere Bell in Wakefield, Mass

- Revere Bells Woodstock VT

-

Bostonians

- Edward F Alexander of The Harvard 20th Civil War Regiment

- Polly Baker

- John Wilkes Booth

- The Mad Hatter, Thomas, Boston Corbett who Killed John Wilkes Booth

- Richard-Henry-Dana-Jr

- James Franklin

- Benjamin Harris of Publick Occurrences

- Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr.

- William Lloyd Garrison

- USS Thomas Hudner DDG116

- Edward Hutchinson Robbins Revere

- Amos Lincoln

- King Philip

- Mayor's of Boston

- Mum Bett & Theodore Sedgwick

- James Otis

- Paul Joseph Revere

- Reverend Larkin's Horse

- John Rowe >

- Be Proud to be Called a Lucy Stoner

- Rachel Wall , Pirate

- Paul Revere the Coroner of Boston

- Deborah Sampson

- Who was Mrs. Silence Dogood?

- Dr. Joseph Warren's Dedication

- History Blog

- Lilja's of Natick

-

Collage of Boston

- 4th of July Parade, Bristol RI

- Boston Harbor

- The Customs House

- Forest Hills Cemetery

- Georges Island

- Nonviolent Monument to Peace - Sherborn

- The Battle Road

- Skate bike and scooter park

- Cassin Young & USS Cassin Young

- MIT

- Historic Charles River

- The Roxbury Standpipe on Fort Hill

- John & Abigail Adams National Park

- Boston's Racial History - Ante-Bellum

- New Page

The Last Woman Hanged in Massachusetts

Was Not Convicted of Witchcraft!

Rachel (Schmidt) Wall 1760-October 8, 1789

The Witch Trials had tainted Massachusetts history and legal decisions since 1692. The city of Salem hanged fifteen women, allowing four others to die in prison. Lest we forget, they also hanged five men associated with witchcraft. Out of disdain for this practice, as much for the treatment of women, and other financial inequities, The King of England, William III, revoked the Massachusetts Bay Colony Charter to end Puritan religious abuses.

Boston was now free to establish common law based on court judgments and jury opinions. To this time, the law permitted a woman that delivered a baby outside wedlock to be hanged. The responsible male partner was exempt or nullified by his jury of peers. Only men sat on juries. As Common Law evolved hangings for witchcraft ended but a select number of women were still hanged between 1691 and 1735, for adultery or childbirth outside of marriage or other felonies. Unfortunately, it took the Common Law years to address all legal prejudices towards women.

In more than 200 years, 127 women were hanged in New England. Rachel Wall was the last woman hanged in Massachusetts on October 8, 1789. If we can be politically correct, she was alleged to be a pirate but was judged to be a thief, committing several physical assaults. Yet, her background provides no link to her vices.

Rachel was born in Carlisle Pennsylvania in 1760. At trial, she stated her father was a farmer, and she was raised Presbyterian. Hearsay suggested her maiden name was Schmidt. She said at trial that her parents gave her a good education. This would imply they provided a good home, schooling, and religion.[i] She married George Wall, and they moved to New York and then Boston. Her husband joined the American Revolutionary Army leaving her to support herself. On his return, the company they kept led to her eventual demise.[ii]

In her words to the court, provided by Daniel Williams in his book Pillars of Salt:

"I acknowledge myself to have been guilty of a great many crimes, such as Sabbath-breaking, stealing, lying, disobedience to parents, and almost every other sin a person could commit, except murder . . . .

In short, the many small crimes I have committed, are too numerous to mention . . . And therefore a particular narrative of them here would serve to extend a work of this kind to too great a length . . . .”

It appears to most historians that George, her husband, was a licensed privateer during the American Revolution, but neither the English nor the American governments offered licenses after the war ended in 1783. George now applied his experience to making a living. Any commercial vessel was a target of his crimes on the ocean. Rachel in tattered clothing may have been the bait to lore vessels to her aide as she waved in distress from George’s schooner. Below decks, the pirates waited to board the unsuspecting and ill-prepared commercial ship. Author, Cindy Vallor, described the manner of deception;

“If the would-be rescue vessel had a small crew that the pirates could easily subdue, they waited until the two ships were tied together, then they boarded the merchant ship and killed her captain and crew. If the rescuers outnumbered George and his mates, Wall refused the offer of passage aboard the merchant vessel and invited her master and first mate to come aboard, supposedly to offer what assistance they could to make repairs. Once the men went below to survey the schooner’s damage, they were murdered. Then George and the men either slipped aboard the rescue ship and slaughtered the remaining crewmembers, or invented a plausible excuse for more sailors from the merchant crew to come aboard the schooner. In turn, these men also met their doom. Once all the merchant crew was dead, George and his friends weighted down the bodies then heaved them over the side. After they plundered the merchantman of any cargo and personal items of value, they scuttled her so that both crew and vessel were never seen again. George deduced, and rightly so that people ashore would assume the ship went down during the storm.” [iii]

Though no reference was cited, Cindy Vallor suggested a couple of dozen men between 1783 and 1788, were murdered by George and his crew. George never made it to trial. A hurricane caught his schooner off shore, and he was swept overboard and drowned.

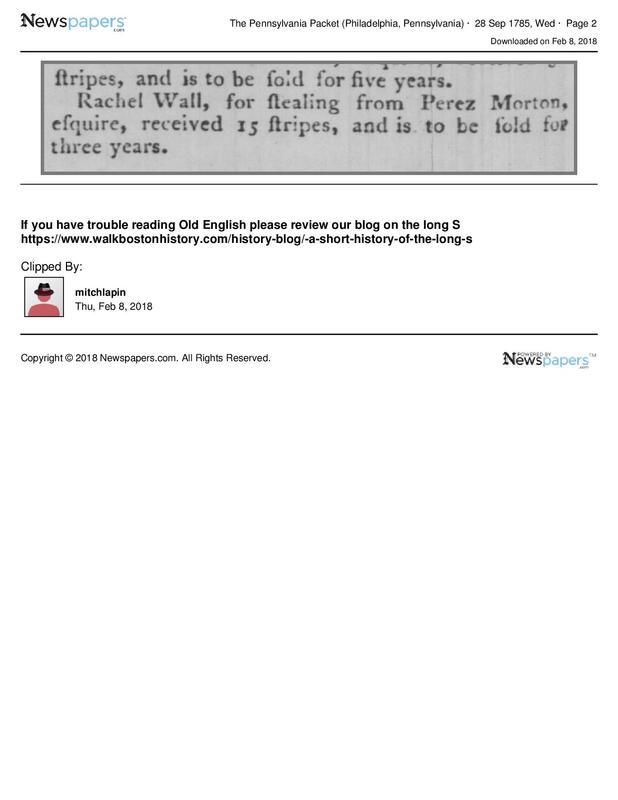

Rachel survived another four years. She was adept at stealing valuables on ships docked at numerous Boston wharfs, typically in the middle of the night.[iv] As ships’ captains learned to secure their valuables, she turned to random assaults on unaccompanied women. Twice she was lashed, fined and indentured to the highest bidder. View the newspaper clipping below. This did not stop her crime spree. In the end, she was arrested in the act a third time and sent to trial where she received the death sentence. She proclaimed her innocence. Here is the account of the last robbery from the Massachusetts Sentinel newspaper.

A singular kind of robbery, for this part of the world, took place on Friday evening last : As a woman was walking alone, she was met by another woman, who seized hold of her and stopped her mouth with her handkerchief, and tore from her head her bonnet and cushion, after which she flung her down, took her shoes and buckles, and then fled. She was soon overtaken and committed to jail [v]

Rachel’s attorneys pleaded for a lesser charge on the claim that Rachel’s victim actually maintained possession of her bonnet, used by Rachel to drag the victim to the ground. The hat was valued at seven shillings equal to slightly more than one-third of an English pound. While British currency was deflating in 1789, the value of the hat was hardly the full story.

The Hurricane that consumed her husband and ended her career as a pirate led to an ocean of resentment; or shall we say retribution? Rachel’s trial attracted a notable crowd. The prosecuting attorney was Robert Treate Paine, a signer of the Declaration of Independence. He asked for the death sentence for “a hardened criminal twice before convicted of “feloniously stealing.” A chief witness was Colonel Thomas Dawes, a Revolutionary hero, architect, a neighbor of John Adams, cousin to William Dawes[vi] and good friend of John Hancock. Though there were five presiding judges, John Hancock, Governor of Massachusetts signed the death sentence. It is easy to speculate that her crimes on the ocean fueled the ultimate judgement for the felonies committed on land. Specifics of the trial can be found at the Superior Court records in the Massachusetts State Archives, microfilm.

Rachel was hanged with two other criminals on October 10, 1789, in the Boston Common. All three criminals were found guilty of highway robbery, according to the Massachusetts Sentinel (Centinel).

P.S. Cindy Vallor makes some interesting suggestions. Rachel did not confess to piracy even on the gallows, according to the local newspapers of the day. At trial, Rachel testified that her husband had left her, suggesting she had no indication of his drowning. Other sources indicated that she did admit at trial to her piracy and did survive the hurricane along with other crew members.

Our perspective is, if her husband and entire crew died at sea in a hurricane, Rachel should have suffered the same fate if she was pirating that day. Was she a part time pirate or lucky to have missed this voyage? Or none of the above?

Our other blogs that further define the moral arguments of the 18th C.

http://www.walkbostonhistory.com/history-blog/-the-unmasking-of-mrs-silence-dogood

http://www.walkbostonhistory.com/history-blog/paul-reveres-inquests-indicts-four-parents-for-infanticide-the-superior-court-jurys-acquit-all

Endnotes;

[i] Parraphrasing: In Pillars of Salt, Williams cites two sources – The Boston Gazette (14 September 1789) and The Massachusetts Centinel (12 September 1789) Madison House, 1993.

[ii] Paraphrasing In Pillars of Salt, Williams cites two sources – The Boston Gazette (14 September 1789) and The Massachusetts Centinel (12 September 1789) Madison House, 1993. Page 284.

[iii] Vallor, Cindy . "Pirates and Privateers." 2012. Accessed August 25, 2017.

http://www.cindyvallar.com/RachelWall.html#Two

[iv] Rob Ossian, at http://www.thepirateking.com/bios/wall_rachel.htm, suggests ship planking is too noisy for anyone to sneak onboard without detection. He does confirm the practice of appearing to be a distressed vessel to attract a commercial ship for plunder.

[iv] The Massachusetts Sentinel a/k/a Massachusetts Centinel reported on the day she was hanged, October 10, 1789

[vi] Co-rider with Paul Revere April 18th, 1775, to alarm the country-side that the “regulars were out.”

[VII] http://www.annebonnypirate.com/page/contact/

http://www.history.com/news/history-lists/5-notorious-female-pirates

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Women_in_piracy

- Guided Tours

- Self Guide Smartphone Tour

-

Revere Bells Index

- The Stickney Revere Bell Listings of 1976

- Ashby Mass. Revere Bell

- Paul Revere Bell of Beverly

- Revere Bells in Boston >

- California's 2 Paul Revere Bells

- Paul Revere & Son's Bell Westborough Massachusetts

- Falmouth, Massachusetts

- Revere Bell Fredericksburg VA

- Revere Bell Hampton NH

- First Parish Church of Kennebunk

- Revere Bells in Maine

- Revere Bell in Mansfield

- Revere Bell of Michigan

- Revere Salem Mass Bell

- Roxbury First Unitariarn Universalist Church and their Revere Bell

- Revere & Son Bell, Savannah Georgia

- Singapore Revere Bell

- Tuscaloosa Bell >

- Revere Bells Lost in Time

- Revere Bells Washington DC

- Revere Bell in Wakefield, Mass

- Revere Bells Woodstock VT

-

Bostonians

- Edward F Alexander of The Harvard 20th Civil War Regiment

- Polly Baker

- John Wilkes Booth

- The Mad Hatter, Thomas, Boston Corbett who Killed John Wilkes Booth

- Richard-Henry-Dana-Jr

- James Franklin

- Benjamin Harris of Publick Occurrences

- Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr.

- William Lloyd Garrison

- USS Thomas Hudner DDG116

- Edward Hutchinson Robbins Revere

- Amos Lincoln

- King Philip

- Mayor's of Boston

- Mum Bett & Theodore Sedgwick

- James Otis

- Paul Joseph Revere

- Reverend Larkin's Horse

- John Rowe >

- Be Proud to be Called a Lucy Stoner

- Rachel Wall , Pirate

- Paul Revere the Coroner of Boston

- Deborah Sampson

- Who was Mrs. Silence Dogood?

- Dr. Joseph Warren's Dedication

- History Blog

- Lilja's of Natick

-

Collage of Boston

- 4th of July Parade, Bristol RI

- Boston Harbor

- The Customs House

- Forest Hills Cemetery

- Georges Island

- Nonviolent Monument to Peace - Sherborn

- The Battle Road

- Skate bike and scooter park

- Cassin Young & USS Cassin Young

- MIT

- Historic Charles River

- The Roxbury Standpipe on Fort Hill

- John & Abigail Adams National Park

- Boston's Racial History - Ante-Bellum

- New Page