Richard Henry Dana Jr. of Two Years Before the Mast and the Boston Fugitive Slave Riots

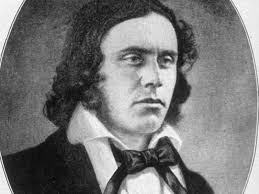

1815 Born in Cambridge Massachusetts and died August 6, 1882, in Rome

1833 left Harvard due to vision issues caused by measles

1834 Sailed from Boston on the brig Pilgrim

1835 Stopped at Santa Barbara, California; worked his way up the coast at land-based jobs

1836 Sailed back to Boston and re-entered Harvard graduating in the class of 1837

1840 Graduated Harvard Law School to practice law (a/k/a) Dane Law School

1840 Published Two Years Before the Mast

1841 Specialized in maritime law and seamen’s rights

1841 Dana published The Seaman's Friend, which became a standard reference on the legal rights and responsibilities of sailors. He defended many seamen pro bono in court

1841 Married Sally Watson

1854 Ten day defense of imprisoned slave Anthony Burns: the third Boston slave riot

1859 Traveled to Cuba and wrote To Cuba and Back at a time the U.S. considered Annexing Cuba

1860 Finished an around the world trip

1861 Appointed by President Lincoln to be the United States district attorney for Massachusetts

Arguing successfully at U.S. Supreme Court that the U. S. had the right to blockade the South

1868 Unsuccessful run for the U. S. House of Representatives

1868 Filed indictment papers for treason against former President of the Confederacy, Jefferson Davis

1876 Nominated to be Ambassador to England; blocked by political enemies

1878 Retired to France to write books on international law

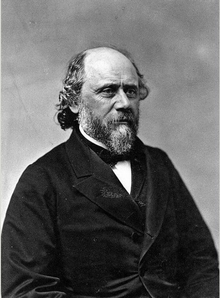

1882 Continued writing on international law and died in Rome of pneumonia

He was America's Most Underrated Legal Scholar and Advocate

The Dana family supplied colonial and antebellum Boston with generations of lawyers, judges, and authors. Richard Henry Dana Jr. made his mark as a defender of fugitive slaves and indentured seamen. Dana’s grandfather, Francis (4th) was well known as a delegate to the Continental Congress and a lawyer and statesman. Francis was sent to England in 1775 to settle differences with our English cousins. He signed the Articles of Confederation in 1778 and served on the Supreme Court of Massachusetts for many years. Francis’ son, Henry Dana Sr., was a well-respected writer, poet, and non-practicing lawyer.

Last year, during a leisure trip to California we discovered a town named after Richard Henry Dana, Jr. The town lies on the ocean halfway between LA and San Diego. Dana Jr. sailed into Dana Point in 1835 on the commercial vessel Pilgrim. Dana Point was originally named Capistrano Bay and was part of Mexico. The Pilgrim had completed the difficult passage around Cape Horn. The motive of the voyage was to purchase raw hides, cure them, and return to Boston. Every sailor on board was required to participate in the long curing process. The Captain of the Pilgrim had total authority over the crew. A hide drogher, those that worked the hide tallow trade, was a major occupation in the bay area due to an abundance of sea otters and seals. Under his maritime contract, Dana was required to spend many more months drying hides than sailing to and from California.

Dana marveled at the wildlife, shoreline and native citizens in each of the towns that the Pilgrim visited. During the ships stay in Capistrano Bay, Dana was permitted one hour off to make some notes about the geography and wildlife. He ran all the way to the hillside at the farthest point of Capistrano Bay and sat at the very apex adoring the waves and their play on the landscape. His shipmates, somewhat less cerebral, found it typical of Dana to observe, while they worked. They referred to the spot he camped on as Dana Point.

He further added to the lure of Dana Point as he mastered the art of carrying the wide, flat, heavy hides atop his head. From one steep bluff, which Dana called “the only romantic spot on the coast,” he tossed the hides onto the beach to dry like giant Frisbees.

Dana Point was preserved as Richard Dana sketched it until real estate development began in the 1920s. As the area settled, the residents desired their own identity and government. In 1959 an attempt to incorporate failed. Neighboring towns attempted to annex Dana Point. The effort to incorporate was renewed successfully in 1987.

On January 1, 1989, the City of Dana Point held an inauguration ceremony on board the brig Pilgrim. Like its predecessor the brig sailed around Cape Horn. The first action taken by the city council was to authorize a city seal. You guessed it. The design above was of Richard Henry Dana, Jr. looking across the harbor at the Pilgrim.

Dana’s sailing adventure was bookended by his education at Harvard. His first undergraduate attempt was aborted by a bout with measles that impacted his vision. On his return from his sea voyage two years later, to Massachusetts from California, he re-entered Harvard. He graduated from law school in 1837 and joined a private practice as an apprentice lawyer. During this period Dana re-wrote the diary of his ocean passage and published his memoirs, Two Years Before the Mast. Of his writing, Herman Melville exclaimed in his White-Jacket:

"But if you want the best idea of Cape Horn, get my friend Dana's unmatchable Two Years Before the Mast. But you can read, and so you must have read it. His chapters describing Cape Horn must have been written with an icicle."[1]

Throughout the 1840s Dana’s practice of law defended the oppressed seamen. A pattern had begun on the schooner Pilgrim as Captain Thompson "got thoroughly out of humor"[2] using flogging for modest offenses. Dana was a crew member and viewed marine discipline from his bunk in the forecastle that housed the lowest seamen; a frame of reference that never deserted him through his entire law practice. Consequently, he made many enemies among the merchant class defending seamen.

Below is an example of his often expressed social conscience.

“In the October 1839 issue of a magazine, he took a local judge, one of his own instructors in law school, to task for letting off a ship's captain and mate with a slap on the wrist for murdering the ship's cook, beating him to death for not "laying hold" of a piece of equipment. The judge had sentenced the captain to ninety days in jail and the mate to thirty days.”[3]

Dana’s greatest gift to Boston and his country began in the 1850s with the three fugitive slave arrests. As a lawyer, he spent the better part of his days in the courthouse located at Court Square, Boston. The granite three story building held the state supreme court, a lock-up, and rooms rented to the federal district court. With Dana’s conscience for the repressed, he could not help but represent Shadrach Minchin, Tom Sims and Anthony Burns, pro-Bono.

Dana collaborated with Minchin’s attorney, Robert Morris. Morris was the second black lawyer admitted to the bar in Massachusetts. He was a principal in challenging the concept of “separate but equal” at the Massachusetts Supreme Court in 1853, on behalf of an African American family that was forced to send their daughter to a segregated school.

Together, Dana and Morris drafted a habeas corpus writ to address Minchin’s civil rights. The motion was an attempt to move the legal issue from a replevin of property to the Bill of Rights. The sitting judge Lemuel Shaw denied the motion that soon became mute. Independent of the legal action a group of two dozen free African Americans assaulted the lock-up and freed Minchin. Federal officials, with carte blanche warrants, tore Boston apart looking for Minchin. Eventually, he was moved to Concord, Massachusetts and then to safety in Canada.

A month later federal authorities arrested Robert Morris claiming he conspired with Shadrach’s rescuers. At trial, Dana spoke for five hours on the excesses of the law and its effots to make Morris a scapegoat. Dana had a few expressive thoughts about Massachusetts own son, Daniel Webster, and his collusion with the compromised fugitive slave law. Once again he spoke his mind in defense of the politically underprivileged. As a result, his enemies list enlarged.

By now, Boston recognized that the South had targeted the Boston as a testing ground of the slave law, to punish them for their radical abolitionist views. One month after the successful defense of Morris, Dana volunteered to defend the second fugitive arrested, Tom Sims, a waiter on Beacon Hill. Sims resisted arrest and stabbed a policeman in the scuffle that ensued as he was leaving work. Again, Judge Shaw refused Dana’s writ of habeas corpus designed to give Sims the legal rights of a citizen. In failing to achieve this, Sims was not permitted to give testimony on his behalf under the writ of replevin that treated him as property to be repossessed. Proof of ownership was the issue to be adjudicated. At this hearing the vilified Daniel Webster, a Boston native and U.S. Senator, spoke on behalf of the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850.

Sims was escorted back to Savannah, Georgia by a deputy marshal. On this return voyage, Sims often asked for a knife to end his life. On arrival in Savannah, he was publicly whipped thirty-nine times and sold off to Mississippi. In 1863 Sims escaped again and made his way back to Boston. The federal marshal that accompanied Sims to Georgia was Charles Devens. He regretted each moment of that journey of rendition. Several years later Devens was appointed the United States Attorney General of Massachusetts. He hired Sims to work for the Federal Department of Justice beginning in 1877.[4]

The third involvement of Dana in the Fugitive Slave Law (FSL) occurred in 1854 upon the arrest in Boston of Anthony Burns. Dana had the benefit of the prior two attempts to sharpen his defense of a fugitive slave. Burns was arrested under a pretense that he was the perpetrator in a violent crime. He was vastly outnumbered but he went peacefully thinking that the mistaken identity would be resolved. As Burns arrived at the courthouse his master and the last renter of Burn’s service, were both present to sign a writ of replevin and establish Burns' identity (as property).

Burns was guarded on the second floor of the courthouse. The first floor was secured with a nautical strength chain and bars were installed on all windows. Adding to the irony Burns’ hands and feet were shackled. Dana motioned for time to prepare his case against the FSL. In the interim, a rescue attempt was made by nearly 5,000 raging abolitionists. They made it through the entrance way and were confronted by 200 armed United States marshals. A shot was fired and James Batchelder, a deputized marshal, was stabbed to death and the rescue effort dissolved.

The murder of Batchelder seemed to stiffen the position of the U.S. attorney general. Recently elected Franklin Pierce, from New Hampshire, fourteenth President of the United States, often interjected in the case to assure the FSL was upheld. Habeas corpus took second place to the search for the murderer. Unfortunately, a replevin motion about Anthony Burns had been before Judge Loring. He was obligated to enforce a law passed by Congress and supported by Pierce with federal troops in Boston. Dana argued that such an action of replevin violated the Massachusetts Constitution since it had eliminated slavery in 1780. Over the next ten days a battle of state versus federal law played out in Judge Loring's court. President Pierce ensured that federal law would be enforced including the use of force to ensure Burn’s imprisonment and delivery to a schooner in Boston harbor to complete Burn’s the rendition.

At this period in Boston a jury of Burns' peers would certainly have freed him. But a jury trial was not an option in replevin of property case. Dana lost the habeas corpus argument but continued to fight on suggesting that the slave master and renter were mistaken in their identity of Burns as the runaway before the court. The date of Burns' escape as presented by the prosecution, seemed to be many days after Burns was employed in Boston. Judge Loring concluded it was simply a dating error and there was no doubt of Burn’s identity and ownership.

In anticipation of a decision in favor of rendition Dana prepared his thoughts on the correct decision. Local papers published it the same morning of Judge Loring’s ruling. It was a thorough review of the Fugitive Slave Law, the Bill of Rights, habeas corpus and Daniel Webster’s controversial compromise with the South in Webster’s speech to Congress of March 7, 1850. Dana's list of enemies grew longer.

On the way home from court Dana was assaulted by a number of men and nearly killed. The perpetrators were believed to be hired local thugs. The likely financiers of this mugging were the Cotton Whigs of Massachusetts linked to the South through the textile trade. After the Civil War, a Massachusetts sheriff traveled to the south and arrested the leader of the gang and brought him back for trial.

Dana by birth was a Boston Brahmin. "His advocacy for the poor and underprivileged," wrote Charles Francis Adams Jr. “.... In the mind of wealthy and respectable Boston, almost anyone was to be preferred to him."[5] Yet his advocacy against the FSL earned him the respect of the federal government in the post Civil War administration.

Dana died in Rome in 1882. Through his entire life he considered his diary, Two Years before the Mast, as a simple youthful passage in time. Melville and Longfellow would literally beg to differ with him. Minchin, Sims, Burns and Lincoln, would point to his actual voyage as the catalyst to a great legal career.

P.S.

Selected works by Dana

Eulogized by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

The Burial of the Poet : RICHARD HENRY DANA

In the old churchyard of his native town,

And in the ancestral tomb beside the wall,

We laid him in the sleep that comes to all,

And left him to his rest and his renown.

The snow was falling, as if Heaven dropped down

White flowers of Paradise to strew his pall;--

The dead around him seemed to wake, and call

His name, as worthy of so white a crown.

And now the moon is shining on the scene,

And the broad sheet of snow is written o'er

With shadows cruciform of leafless trees,

As once the winding-sheet of Saladin

With chapters of the Koran; but, ah! more

Mysterious and triumphant signs are these.

Published in The Atlantic 1879 [6]

[1] Levine, Robert S. 1989. Conspiracy and Romance: Studies in Brockden Brown, Cooper, Hawthorne, and Melville. Cambridge University Press.

[2] Richard Henry Dana, by Robert L. Gale, Twayne Publishers, Inc. Library of Congress number 68-24301; also available at Dean College library.

[3] Levine, Robert S. 1989. Conspiracy and Romance: Studies in Brockden Brown, Cooper, Hawthorne, and Melville. Cambridge University Press. P. 282

4. Richard Henry Data, by Robert L. Gale, Twayne Publishers, Inc. Library of Congress number 68-24301; also available at Dean College library.

5 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Sims

6 This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Dana, Francis". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Adams, Charles Francis. 1890. Richard Henry Dana : A biography. 2 vols. Boston: Houghton, Mifflin. Available from Dean College

Buried at:

Campo Cestio

Rome, Città Metropolitana di Roma Capitale, Lazio, Italy

PLOT I 177 A

1833 left Harvard due to vision issues caused by measles

1834 Sailed from Boston on the brig Pilgrim

1835 Stopped at Santa Barbara, California; worked his way up the coast at land-based jobs

1836 Sailed back to Boston and re-entered Harvard graduating in the class of 1837

1840 Graduated Harvard Law School to practice law (a/k/a) Dane Law School

1840 Published Two Years Before the Mast

1841 Specialized in maritime law and seamen’s rights

1841 Dana published The Seaman's Friend, which became a standard reference on the legal rights and responsibilities of sailors. He defended many seamen pro bono in court

1841 Married Sally Watson

1854 Ten day defense of imprisoned slave Anthony Burns: the third Boston slave riot

1859 Traveled to Cuba and wrote To Cuba and Back at a time the U.S. considered Annexing Cuba

1860 Finished an around the world trip

1861 Appointed by President Lincoln to be the United States district attorney for Massachusetts

Arguing successfully at U.S. Supreme Court that the U. S. had the right to blockade the South

1868 Unsuccessful run for the U. S. House of Representatives

1868 Filed indictment papers for treason against former President of the Confederacy, Jefferson Davis

1876 Nominated to be Ambassador to England; blocked by political enemies

1878 Retired to France to write books on international law

1882 Continued writing on international law and died in Rome of pneumonia

He was America's Most Underrated Legal Scholar and Advocate

The Dana family supplied colonial and antebellum Boston with generations of lawyers, judges, and authors. Richard Henry Dana Jr. made his mark as a defender of fugitive slaves and indentured seamen. Dana’s grandfather, Francis (4th) was well known as a delegate to the Continental Congress and a lawyer and statesman. Francis was sent to England in 1775 to settle differences with our English cousins. He signed the Articles of Confederation in 1778 and served on the Supreme Court of Massachusetts for many years. Francis’ son, Henry Dana Sr., was a well-respected writer, poet, and non-practicing lawyer.

Last year, during a leisure trip to California we discovered a town named after Richard Henry Dana, Jr. The town lies on the ocean halfway between LA and San Diego. Dana Jr. sailed into Dana Point in 1835 on the commercial vessel Pilgrim. Dana Point was originally named Capistrano Bay and was part of Mexico. The Pilgrim had completed the difficult passage around Cape Horn. The motive of the voyage was to purchase raw hides, cure them, and return to Boston. Every sailor on board was required to participate in the long curing process. The Captain of the Pilgrim had total authority over the crew. A hide drogher, those that worked the hide tallow trade, was a major occupation in the bay area due to an abundance of sea otters and seals. Under his maritime contract, Dana was required to spend many more months drying hides than sailing to and from California.

Dana marveled at the wildlife, shoreline and native citizens in each of the towns that the Pilgrim visited. During the ships stay in Capistrano Bay, Dana was permitted one hour off to make some notes about the geography and wildlife. He ran all the way to the hillside at the farthest point of Capistrano Bay and sat at the very apex adoring the waves and their play on the landscape. His shipmates, somewhat less cerebral, found it typical of Dana to observe, while they worked. They referred to the spot he camped on as Dana Point.

He further added to the lure of Dana Point as he mastered the art of carrying the wide, flat, heavy hides atop his head. From one steep bluff, which Dana called “the only romantic spot on the coast,” he tossed the hides onto the beach to dry like giant Frisbees.

Dana Point was preserved as Richard Dana sketched it until real estate development began in the 1920s. As the area settled, the residents desired their own identity and government. In 1959 an attempt to incorporate failed. Neighboring towns attempted to annex Dana Point. The effort to incorporate was renewed successfully in 1987.

On January 1, 1989, the City of Dana Point held an inauguration ceremony on board the brig Pilgrim. Like its predecessor the brig sailed around Cape Horn. The first action taken by the city council was to authorize a city seal. You guessed it. The design above was of Richard Henry Dana, Jr. looking across the harbor at the Pilgrim.

Dana’s sailing adventure was bookended by his education at Harvard. His first undergraduate attempt was aborted by a bout with measles that impacted his vision. On his return from his sea voyage two years later, to Massachusetts from California, he re-entered Harvard. He graduated from law school in 1837 and joined a private practice as an apprentice lawyer. During this period Dana re-wrote the diary of his ocean passage and published his memoirs, Two Years Before the Mast. Of his writing, Herman Melville exclaimed in his White-Jacket:

"But if you want the best idea of Cape Horn, get my friend Dana's unmatchable Two Years Before the Mast. But you can read, and so you must have read it. His chapters describing Cape Horn must have been written with an icicle."[1]

Throughout the 1840s Dana’s practice of law defended the oppressed seamen. A pattern had begun on the schooner Pilgrim as Captain Thompson "got thoroughly out of humor"[2] using flogging for modest offenses. Dana was a crew member and viewed marine discipline from his bunk in the forecastle that housed the lowest seamen; a frame of reference that never deserted him through his entire law practice. Consequently, he made many enemies among the merchant class defending seamen.

Below is an example of his often expressed social conscience.

“In the October 1839 issue of a magazine, he took a local judge, one of his own instructors in law school, to task for letting off a ship's captain and mate with a slap on the wrist for murdering the ship's cook, beating him to death for not "laying hold" of a piece of equipment. The judge had sentenced the captain to ninety days in jail and the mate to thirty days.”[3]

Dana’s greatest gift to Boston and his country began in the 1850s with the three fugitive slave arrests. As a lawyer, he spent the better part of his days in the courthouse located at Court Square, Boston. The granite three story building held the state supreme court, a lock-up, and rooms rented to the federal district court. With Dana’s conscience for the repressed, he could not help but represent Shadrach Minchin, Tom Sims and Anthony Burns, pro-Bono.

Dana collaborated with Minchin’s attorney, Robert Morris. Morris was the second black lawyer admitted to the bar in Massachusetts. He was a principal in challenging the concept of “separate but equal” at the Massachusetts Supreme Court in 1853, on behalf of an African American family that was forced to send their daughter to a segregated school.

Together, Dana and Morris drafted a habeas corpus writ to address Minchin’s civil rights. The motion was an attempt to move the legal issue from a replevin of property to the Bill of Rights. The sitting judge Lemuel Shaw denied the motion that soon became mute. Independent of the legal action a group of two dozen free African Americans assaulted the lock-up and freed Minchin. Federal officials, with carte blanche warrants, tore Boston apart looking for Minchin. Eventually, he was moved to Concord, Massachusetts and then to safety in Canada.

A month later federal authorities arrested Robert Morris claiming he conspired with Shadrach’s rescuers. At trial, Dana spoke for five hours on the excesses of the law and its effots to make Morris a scapegoat. Dana had a few expressive thoughts about Massachusetts own son, Daniel Webster, and his collusion with the compromised fugitive slave law. Once again he spoke his mind in defense of the politically underprivileged. As a result, his enemies list enlarged.

By now, Boston recognized that the South had targeted the Boston as a testing ground of the slave law, to punish them for their radical abolitionist views. One month after the successful defense of Morris, Dana volunteered to defend the second fugitive arrested, Tom Sims, a waiter on Beacon Hill. Sims resisted arrest and stabbed a policeman in the scuffle that ensued as he was leaving work. Again, Judge Shaw refused Dana’s writ of habeas corpus designed to give Sims the legal rights of a citizen. In failing to achieve this, Sims was not permitted to give testimony on his behalf under the writ of replevin that treated him as property to be repossessed. Proof of ownership was the issue to be adjudicated. At this hearing the vilified Daniel Webster, a Boston native and U.S. Senator, spoke on behalf of the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850.

Sims was escorted back to Savannah, Georgia by a deputy marshal. On this return voyage, Sims often asked for a knife to end his life. On arrival in Savannah, he was publicly whipped thirty-nine times and sold off to Mississippi. In 1863 Sims escaped again and made his way back to Boston. The federal marshal that accompanied Sims to Georgia was Charles Devens. He regretted each moment of that journey of rendition. Several years later Devens was appointed the United States Attorney General of Massachusetts. He hired Sims to work for the Federal Department of Justice beginning in 1877.[4]

The third involvement of Dana in the Fugitive Slave Law (FSL) occurred in 1854 upon the arrest in Boston of Anthony Burns. Dana had the benefit of the prior two attempts to sharpen his defense of a fugitive slave. Burns was arrested under a pretense that he was the perpetrator in a violent crime. He was vastly outnumbered but he went peacefully thinking that the mistaken identity would be resolved. As Burns arrived at the courthouse his master and the last renter of Burn’s service, were both present to sign a writ of replevin and establish Burns' identity (as property).

Burns was guarded on the second floor of the courthouse. The first floor was secured with a nautical strength chain and bars were installed on all windows. Adding to the irony Burns’ hands and feet were shackled. Dana motioned for time to prepare his case against the FSL. In the interim, a rescue attempt was made by nearly 5,000 raging abolitionists. They made it through the entrance way and were confronted by 200 armed United States marshals. A shot was fired and James Batchelder, a deputized marshal, was stabbed to death and the rescue effort dissolved.

The murder of Batchelder seemed to stiffen the position of the U.S. attorney general. Recently elected Franklin Pierce, from New Hampshire, fourteenth President of the United States, often interjected in the case to assure the FSL was upheld. Habeas corpus took second place to the search for the murderer. Unfortunately, a replevin motion about Anthony Burns had been before Judge Loring. He was obligated to enforce a law passed by Congress and supported by Pierce with federal troops in Boston. Dana argued that such an action of replevin violated the Massachusetts Constitution since it had eliminated slavery in 1780. Over the next ten days a battle of state versus federal law played out in Judge Loring's court. President Pierce ensured that federal law would be enforced including the use of force to ensure Burn’s imprisonment and delivery to a schooner in Boston harbor to complete Burn’s the rendition.

At this period in Boston a jury of Burns' peers would certainly have freed him. But a jury trial was not an option in replevin of property case. Dana lost the habeas corpus argument but continued to fight on suggesting that the slave master and renter were mistaken in their identity of Burns as the runaway before the court. The date of Burns' escape as presented by the prosecution, seemed to be many days after Burns was employed in Boston. Judge Loring concluded it was simply a dating error and there was no doubt of Burn’s identity and ownership.

In anticipation of a decision in favor of rendition Dana prepared his thoughts on the correct decision. Local papers published it the same morning of Judge Loring’s ruling. It was a thorough review of the Fugitive Slave Law, the Bill of Rights, habeas corpus and Daniel Webster’s controversial compromise with the South in Webster’s speech to Congress of March 7, 1850. Dana's list of enemies grew longer.

On the way home from court Dana was assaulted by a number of men and nearly killed. The perpetrators were believed to be hired local thugs. The likely financiers of this mugging were the Cotton Whigs of Massachusetts linked to the South through the textile trade. After the Civil War, a Massachusetts sheriff traveled to the south and arrested the leader of the gang and brought him back for trial.

Dana by birth was a Boston Brahmin. "His advocacy for the poor and underprivileged," wrote Charles Francis Adams Jr. “.... In the mind of wealthy and respectable Boston, almost anyone was to be preferred to him."[5] Yet his advocacy against the FSL earned him the respect of the federal government in the post Civil War administration.

Dana died in Rome in 1882. Through his entire life he considered his diary, Two Years before the Mast, as a simple youthful passage in time. Melville and Longfellow would literally beg to differ with him. Minchin, Sims, Burns and Lincoln, would point to his actual voyage as the catalyst to a great legal career.

P.S.

- The Pilgrim burned at sea in 1856. The ship was built in 1825, owned by Bryan, Sturgis & Co., merchants in the China and California hide trade. Sturgis was a member of the Massachusetts Historical Society, possessor of an original copy of Two Years before the Mast. William Sturgis journal, waste books and ledgers are stored at the Harvard University Business School in the Baker Library.

- The replica of the Pilgrim in the harbor at Dana Point is actually a brig, downgraded from a three masted schooner to serve as a training vessel.

- The hide droghers sculpture by John R. Terken, 1972 was sponsored by the San Juan Capistrano Historical Society prior to the incorporation of the City of Dana Point

- If you are sailing to Dana Point N 33° 27.499 W 117° 41.999 11S E 434950 N 3702317

- If you are a sailor, Dana's book, The Seamen's Friend, might answer all your nautical questions

- The forty-niners rushing to California carried Two Years Before the Mast as their Bill of Rights.[6]

- Dana's cousin lost his original sea diary. His most famous book came mostly from memory

Selected works by Dana

- 1840. Two Years Before the Mast . Revised 1869 by the author; revised 1911 by his son.

- 1841. The Seaman's Friend: Containing a Treatise on Practical Seamanship, with Plates; A Dictionary of Sea Terms; Customs and Usages of the Merchant Service; Laws Relating to the Practical Duties of Master and Mariners. 1st edition; 6th edition, 1851

- 1842. An Autobiographical Sketch.

- 1859. To Cuba and Back.

- 1869. Twenty-Four Years After. Now included in subsequent editions of Two Years Before the Mast

Eulogized by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

The Burial of the Poet : RICHARD HENRY DANA

In the old churchyard of his native town,

And in the ancestral tomb beside the wall,

We laid him in the sleep that comes to all,

And left him to his rest and his renown.

The snow was falling, as if Heaven dropped down

White flowers of Paradise to strew his pall;--

The dead around him seemed to wake, and call

His name, as worthy of so white a crown.

And now the moon is shining on the scene,

And the broad sheet of snow is written o'er

With shadows cruciform of leafless trees,

As once the winding-sheet of Saladin

With chapters of the Koran; but, ah! more

Mysterious and triumphant signs are these.

Published in The Atlantic 1879 [6]

[1] Levine, Robert S. 1989. Conspiracy and Romance: Studies in Brockden Brown, Cooper, Hawthorne, and Melville. Cambridge University Press.

[2] Richard Henry Dana, by Robert L. Gale, Twayne Publishers, Inc. Library of Congress number 68-24301; also available at Dean College library.

[3] Levine, Robert S. 1989. Conspiracy and Romance: Studies in Brockden Brown, Cooper, Hawthorne, and Melville. Cambridge University Press. P. 282

4. Richard Henry Data, by Robert L. Gale, Twayne Publishers, Inc. Library of Congress number 68-24301; also available at Dean College library.

5 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Sims

6 This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Dana, Francis". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Adams, Charles Francis. 1890. Richard Henry Dana : A biography. 2 vols. Boston: Houghton, Mifflin. Available from Dean College

Buried at:

Campo Cestio

Rome, Città Metropolitana di Roma Capitale, Lazio, Italy

PLOT I 177 A