Edward F. Alexander of Nantucket, Massachusetts

Was MIA September 17, 1862, at Antietam

We have all experienced a moment that endlessly captures our thoughts. My time came while reading a book about Harvard’s Civil War volunteers, also known as the 20th Massachusetts Volunteer Regiment.[i] The Civil War produced thousands of ironic and heartfelt moments, and the Alexander family of Nantucket is another example.

Harvard’s Regiment began in earnest answering President Lincoln’s call to duty. Alumnus and undergraduates immediately enlisted to end the Rebellion. Initially, most officers were abolitionists from the general geographic area around Boston, including two of Paul Revere's grandsons. Civil War regiments needed to recruit 813 volunteers, before the unit could be mustered in by John Andrews, Governor of Massachusetts. Once formed, a regiment was required to replace casualties up to its original level to maintain its distinction. This compelled officers to continually recruit volunteers to replace battlefield losses or surrender control of the regiment and their path to promotion. Often, experienced combat officers had to return to New England to recruit.

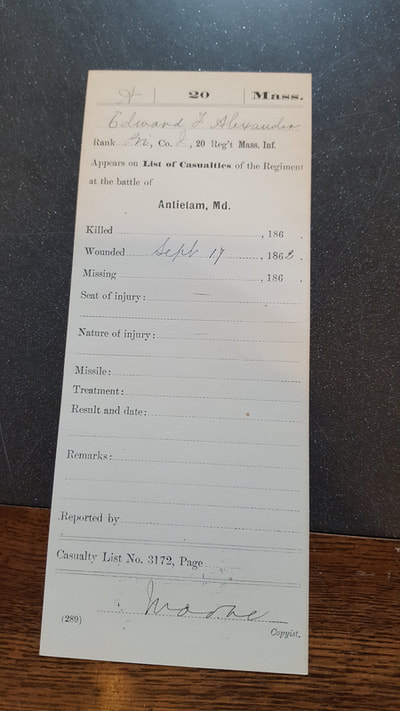

At the Battle of Antietam, on September 17, 1862, the Harvard Regiment lost many professional soldiers from the intellectual class. The non-officer class suffered far greater casualties, but accumulated much less patriotic favor. One private, recruited in Nantucket, was last seen near the fight astride the “West Woods,” at Antietam. Private Edward F. Alexander, 19 years of age, was wounded in the shoulder. His Lieutenant, Leander Alley, repeatedly ordered him to seek medical treatment. At first, Edward refused and continued to fight. Eventually, he conceded to seek help and struggled off towards the West Woods. Typical of most Civil War battles the same territory was fought, won and lost multiple times in a day. This held true of the West Woods. Consequently, Company I of the Harvard Regiment lost contact with Alexander.

Lieutenant Alley, also of Nantucket, was killed in action at Fredericksburg on December 11th of the same year, severing a tenuous thread of information about Alexander. Private Alexander was declared Killed and missing in action. Seven years later, his mother was awarded Edwards pension. The written application and award, on file at the National Archives, offered no clue to his death or final resting place beyond Antietam.

The National Archives research center (NARA), on Constitutional Avenue, Washington D.C., maintains the hard- stock medical records of most Union regiments. Upon review, we found the stack of the Harvard Regiment modestly out of alphabetic order. A medical history existed for Edward F. Alexander near the back of the pile. It confirmed that he made it to the General Hospital in Frederick, Maryland. Sharpsburg, the proximity of the Battle of Antietam is twenty-four miles from Frederick, Maryland. A wounded soldier could not cover that distance without medical support.

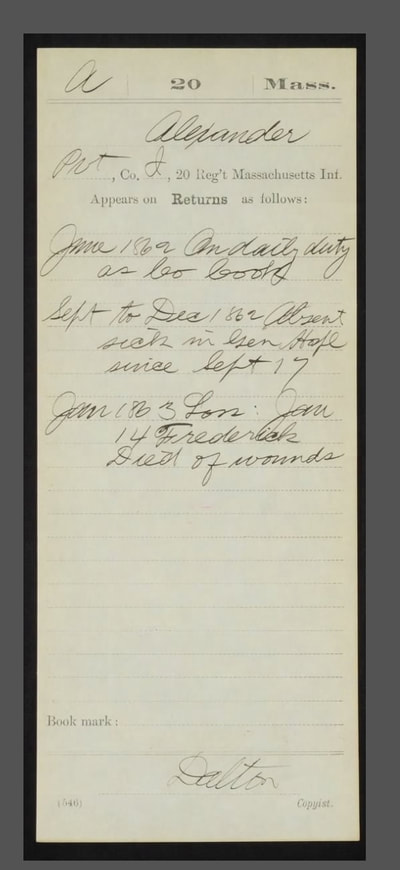

The Civil War archivist at the National Archives, linked us to a private archivist service called Fold3. Scanned into their records was Edward F. Alexander’s death record dated January 14, 1863. It is imaged below. He was under doctor's care since the day he was wounded.

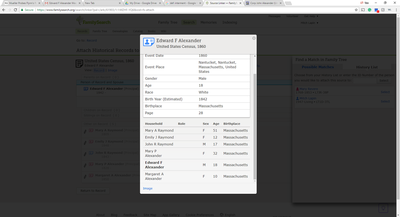

Consequently, our focus changed. We wanted to find his final resting place. We confirmed that he was not buried in his family plot or in the two other cemeteries on Nantucket. Our search was stymied further as the last two family members, his half-sister, Margaret A. Alexander died in 1877, and his stepmother, Mary P. Raymond Alexander (recipient of his pension) died in 1893.[ii]

During a second visit the archivist at NARA further directed us to the Western Maryland Historical Library (WHILBR) Archivists. Their records and that of the National Museum of Civil War Medicine did not find Edward or his burial site in any of the local hospitals or cemeteries. The museum archivists suggested we reach out to the Mount Olivet Cemetery in Frederick, Maryland, near the General hospital and a likely site of interment records. Nothing further could be learned of his grave site.

If you follow the timeline, the irony is apparent. The pension documents listed his date of death as September 17, 1862, at Antietam. To this very day, the Alexander family was not aware that he was hospitalized for another 119 days in Frederick, Maryland, until his death, January 14th, 1863. His family suffered from history's quirk of fate, believing he disappeared in the woods at Antietam.

To-date we have no confirmation of the location of his grave. We hope that a soldier nursed for 119 days after the Antietam battle would not be expediently entombed in an unmarked grave. Dog tags or other identifying documents were not employed during the Civil War. On their own initiative each soldier found an identifying solution if they felt death was imminent. Typically, their name and town was pinned to the back of their uniform by their comrades. Later in the war insignias identifying the soldier's unit were added. If he was unconscious during the entire hospitalization, his identity may not have been known.

Unfortunately, the Battle of Antietam and Fredericksburg overlapped in time and geographic proximity. Alexander’s death came as the Union Army suffered nearly thirteen thousand additional dead or wounded, at Fredericksburg, Virginia, on December 11th-15th, 1862. The two confrontations sent thirty-two-thousand Union soldiers into the military medical system. Antietam alone required 62 different temporary Union hospitals to meet the medical demands of the one day battle.

Our effort to find Alexander’s final resting place was a great learning experience. Additionally, a few revelations about Edward F. Alexander and family, made this effort very personal. He was nineteen years of age, a young shipwright[iii] from the wealthy whaling village of Nantucket, a committed abolitionist, but an artisan among Harvard’s intellectuals. In the end, there is no one left of his family to receive the news of Edwards last 119 days. Hence, we adopted the additional task of finding his burial site hoping for a fitting end to Edward F. Alexander’s history. One-hundred and fifty-five years separate us from the unknown. If anyone has a suggestion to search further for his place of interment, please contact us at [email protected]. Our sources are listed below.

[i] Miller, Richard F. Harvards Civil War: a history of the Twentieth Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry. Hanover, NH, University Press of New England, 2005. P.178.

[ii] Edwards biological mother was Elisabeth Folger, Died November 15, 1847.

[iii] Carpenter working mostly on ships in drydock.

Further reading on the Harvard Regiment

https://www.walkbostonhistory.com/history-blog/-they-marched-to-perfect-the-american-revolution

www.walkbostonhistory.com/history-blog/the-two-grandsons-of-paul-revere-that-fought-in-the-civil-war-to-end-the-compromise-with-slavery

Sources

Was MIA September 17, 1862, at Antietam

We have all experienced a moment that endlessly captures our thoughts. My time came while reading a book about Harvard’s Civil War volunteers, also known as the 20th Massachusetts Volunteer Regiment.[i] The Civil War produced thousands of ironic and heartfelt moments, and the Alexander family of Nantucket is another example.

Harvard’s Regiment began in earnest answering President Lincoln’s call to duty. Alumnus and undergraduates immediately enlisted to end the Rebellion. Initially, most officers were abolitionists from the general geographic area around Boston, including two of Paul Revere's grandsons. Civil War regiments needed to recruit 813 volunteers, before the unit could be mustered in by John Andrews, Governor of Massachusetts. Once formed, a regiment was required to replace casualties up to its original level to maintain its distinction. This compelled officers to continually recruit volunteers to replace battlefield losses or surrender control of the regiment and their path to promotion. Often, experienced combat officers had to return to New England to recruit.

At the Battle of Antietam, on September 17, 1862, the Harvard Regiment lost many professional soldiers from the intellectual class. The non-officer class suffered far greater casualties, but accumulated much less patriotic favor. One private, recruited in Nantucket, was last seen near the fight astride the “West Woods,” at Antietam. Private Edward F. Alexander, 19 years of age, was wounded in the shoulder. His Lieutenant, Leander Alley, repeatedly ordered him to seek medical treatment. At first, Edward refused and continued to fight. Eventually, he conceded to seek help and struggled off towards the West Woods. Typical of most Civil War battles the same territory was fought, won and lost multiple times in a day. This held true of the West Woods. Consequently, Company I of the Harvard Regiment lost contact with Alexander.

Lieutenant Alley, also of Nantucket, was killed in action at Fredericksburg on December 11th of the same year, severing a tenuous thread of information about Alexander. Private Alexander was declared Killed and missing in action. Seven years later, his mother was awarded Edwards pension. The written application and award, on file at the National Archives, offered no clue to his death or final resting place beyond Antietam.

The National Archives research center (NARA), on Constitutional Avenue, Washington D.C., maintains the hard- stock medical records of most Union regiments. Upon review, we found the stack of the Harvard Regiment modestly out of alphabetic order. A medical history existed for Edward F. Alexander near the back of the pile. It confirmed that he made it to the General Hospital in Frederick, Maryland. Sharpsburg, the proximity of the Battle of Antietam is twenty-four miles from Frederick, Maryland. A wounded soldier could not cover that distance without medical support.

The Civil War archivist at the National Archives, linked us to a private archivist service called Fold3. Scanned into their records was Edward F. Alexander’s death record dated January 14, 1863. It is imaged below. He was under doctor's care since the day he was wounded.

Consequently, our focus changed. We wanted to find his final resting place. We confirmed that he was not buried in his family plot or in the two other cemeteries on Nantucket. Our search was stymied further as the last two family members, his half-sister, Margaret A. Alexander died in 1877, and his stepmother, Mary P. Raymond Alexander (recipient of his pension) died in 1893.[ii]

During a second visit the archivist at NARA further directed us to the Western Maryland Historical Library (WHILBR) Archivists. Their records and that of the National Museum of Civil War Medicine did not find Edward or his burial site in any of the local hospitals or cemeteries. The museum archivists suggested we reach out to the Mount Olivet Cemetery in Frederick, Maryland, near the General hospital and a likely site of interment records. Nothing further could be learned of his grave site.

If you follow the timeline, the irony is apparent. The pension documents listed his date of death as September 17, 1862, at Antietam. To this very day, the Alexander family was not aware that he was hospitalized for another 119 days in Frederick, Maryland, until his death, January 14th, 1863. His family suffered from history's quirk of fate, believing he disappeared in the woods at Antietam.

To-date we have no confirmation of the location of his grave. We hope that a soldier nursed for 119 days after the Antietam battle would not be expediently entombed in an unmarked grave. Dog tags or other identifying documents were not employed during the Civil War. On their own initiative each soldier found an identifying solution if they felt death was imminent. Typically, their name and town was pinned to the back of their uniform by their comrades. Later in the war insignias identifying the soldier's unit were added. If he was unconscious during the entire hospitalization, his identity may not have been known.

Unfortunately, the Battle of Antietam and Fredericksburg overlapped in time and geographic proximity. Alexander’s death came as the Union Army suffered nearly thirteen thousand additional dead or wounded, at Fredericksburg, Virginia, on December 11th-15th, 1862. The two confrontations sent thirty-two-thousand Union soldiers into the military medical system. Antietam alone required 62 different temporary Union hospitals to meet the medical demands of the one day battle.

Our effort to find Alexander’s final resting place was a great learning experience. Additionally, a few revelations about Edward F. Alexander and family, made this effort very personal. He was nineteen years of age, a young shipwright[iii] from the wealthy whaling village of Nantucket, a committed abolitionist, but an artisan among Harvard’s intellectuals. In the end, there is no one left of his family to receive the news of Edwards last 119 days. Hence, we adopted the additional task of finding his burial site hoping for a fitting end to Edward F. Alexander’s history. One-hundred and fifty-five years separate us from the unknown. If anyone has a suggestion to search further for his place of interment, please contact us at [email protected]. Our sources are listed below.

[i] Miller, Richard F. Harvards Civil War: a history of the Twentieth Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry. Hanover, NH, University Press of New England, 2005. P.178.

[ii] Edwards biological mother was Elisabeth Folger, Died November 15, 1847.

[iii] Carpenter working mostly on ships in drydock.

Further reading on the Harvard Regiment

https://www.walkbostonhistory.com/history-blog/-they-marched-to-perfect-the-american-revolution

www.walkbostonhistory.com/history-blog/the-two-grandsons-of-paul-revere-that-fought-in-the-civil-war-to-end-the-compromise-with-slavery

Sources

- NARA, United States National Archives, research center Constitution Avenue NW, room 203

- Town Clerk, Nantucket, Massachusetts

- Western Maryland Regional Library (WHILBR) Archivists and

- Mount Olivet Cemetery, Frederick, Maryland

- National Museum of Civil War Medicine, Frederick, Maryland

- Natucket Historical Association https://www.nantuckethistoricalassociation.net/bgr/bgr-o/p43.htm#i1280

- Richard F. Miller, Harvard’s Civil War, Miller, Richard F. Harvards Civil War: a history of the Twentieth Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry. Hanover, NH, University Press of New England, 2005. P.178

- https://www.findagrave.com/cemetery/91483/memorial-search?firstName=Edward&lastName=Alexander&cemeteryname=Prospect+Hill+Cemetery

- “One Vast Hospital” by Terry Reimer, researched by archivists at Mount Olivet Cemetery