- Guided Tours

- Self Guide Smartphone Tour

-

Revere Bells Index

- The Stickney Revere Bell Listings of 1976

- Ashby Mass. Revere Bell

- Paul Revere Bell of Beverly

- Revere Bells in Boston >

- California's 2 Paul Revere Bells

- Paul Revere & Son's Bell Westborough Massachusetts

- Falmouth, Massachusetts

- Revere Bell Fredericksburg VA

- Revere Bell Hampton NH

- First Parish Church of Kennebunk

- Revere Bells in Maine

- Revere Bell in Mansfield

- Revere Bell of Michigan

- Revere Salem Mass Bell

- Roxbury First Unitariarn Universalist Church and their Revere Bell

- Revere & Son Bell, Savannah Georgia

- Singapore Revere Bell

- Tuscaloosa Bell >

- Revere Bells Lost in Time

- Revere Bells Washington DC

- Revere Bell in Wakefield, Mass

- Revere Bells Woodstock VT

-

Bostonians

- Edward F Alexander of The Harvard 20th Civil War Regiment

- Polly Baker

- John Wilkes Booth

- The Mad Hatter, Thomas, Boston Corbett who Killed John Wilkes Booth

- Richard-Henry-Dana-Jr

- James Franklin

- Benjamin Harris of Publick Occurrences

- Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr.

- William Lloyd Garrison

- USS Thomas Hudner DDG116

- Edward Hutchinson Robbins Revere

- Amos Lincoln

- King Philip

- Mayor's of Boston

- Mum Bett & Theodore Sedgwick

- James Otis

- Paul Joseph Revere

- Reverend Larkin's Horse

- John Rowe >

- Be Proud to be Called a Lucy Stoner

- Rachel Wall , Pirate

- Paul Revere the Coroner of Boston

- Deborah Sampson

- Who was Mrs. Silence Dogood?

- Dr. Joseph Warren's Dedication

- History Blog

- Lilja's of Natick

-

Collage of Boston

- 4th of July Parade, Bristol RI

- Boston Harbor

- The Customs House

- Forest Hills Cemetery

- Georges Island

- Nonviolent Monument to Peace - Sherborn

- The Battle Road

- Skate bike and scooter park

- Cassin Young & USS Cassin Young

- MIT

- Historic Charles River

- The Roxbury Standpipe on Fort Hill

- John & Abigail Adams National Park

- Boston's Racial History - Ante-Bellum

- New Page

|

Benjamin Harris was born in London in 1673, and immigrated to New England in 1686, leaving his family behind. He eventually returned to London and died in 1716. He was thoroughly anti-Catholic throughout his life.

His most notable publication The New England Primer, used in every school, made him socially influential. With particularity, Harris attempted to publish Boston's first newspaper on September 25th, 1690, sixty years and two months after the Puritans arrived in Salem. The Publick Occurrence . . . may well have been a most innovative publication. Here is one example; the fourth page was left blank so the readers could write their personal “news” or views before they passed the paper to neighbors. Wouldn't this be fun or scandalous today?? The initial publication detailed suicides, several hostile Indian events, health matters like small-pox, fires, citizens suffering depression, and continued to debauch the French monarch's incestual sleeping habit. Yet, one of his promises in the first and only edition was “towards the Curing, or at least the Charming of that Spirit of Lying, which prevails amongst us.” Unfortunately, four days after the first edition, September 28, 1690, the "Governour Council" shut down the paper, based on "doubtful and uncertain Reports." Harris was the first to lose the initiative. By 1800, over thirty-nine newspapers began and collapsed in Boston. A handful survived into the 19th Century. It was a very risky business. References; By rough count The Boston Public Library, microfilm records had at least 39 different newspapers for the period. I had to give up counting. Here's a tabulation; https://www.colonialsociety.org/publications/301/list-boston-newspapers-years-1704-1780 Massachusetts Historical Society, collection https://www.masshist.org/search?terms=newspapers&start=40&num=10 tracks many of the most influential and enduring papers.

0 Comments

Reverend William Braxton

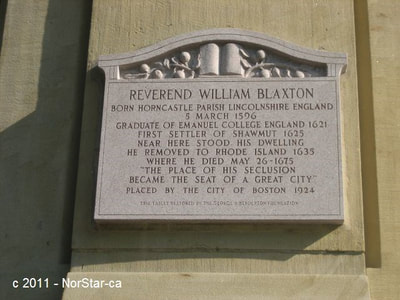

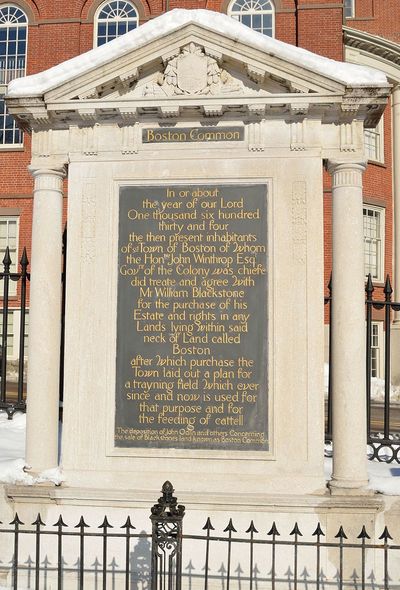

1595-1675 The Reverend arrived in Weymouth, Massachusetts with the Robert Gorges expedition with the notion that the Plimoth Plantation was able and willing to support them for a fee. Unfortunately, the additional one-hundred Gorges further divided the Plantations meager winter rations. Fortunately, the survivors of the Gorges realized they had made a poor investment and by 1625, all but the Reverend returned to England. William Bradford, Governor of the Plimoth Plantation was relieved, as the Gorges were not particularly diplomatic to the native Wampanoag. The Indians were vital to the plantations survival. The Reverend migrated to an area we refer to as the Boston Common. The Shawmut, a segment of the Massachusetts Native Americans, became his friend and helped him find water. There were five natural springs, Mill Creek and the Charles River to support life. He cultivated six acres of land to support him, sharing his produce with the Shawmut. Unlucky for the Reverend, On September 17, 1630, he was engaged by the advance party of the Puritans of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Reverend Braxton was an Episcopalian minister. He supported the Church of England. The Puritans that immigrated to Salem, Massachusetts believed the Church of England was influenced by the Pope. They wanted to restore Christianity to the scriptures and set an example for England to shed its sinful ways. Prompted by The Puritan Way, Reverend Braxton quickly learned that he was his own best company. In negotiations with John Winthrop and the Massachusetts Bay Colony, he sold the fifty acres that became the Boston Common and moved to Blackstone Valley. As so often happened in New England, someone registered the name incorrectly. It should have been the Braxton Valley. To this day this error has been perpetuated. He was not entirely forgotten. Two plaques on Beacon Street, across from the Boston Common, mark his impact on the area. Above is the 1924 and most recently dedicated plaque at the corner of Tremont and Union Street. The error has been perpetuated. In a light hearted sense Reverend Braxton really did not have a title or a charter to the 50 acres of the Boston Common. Could this have been the first fraudulent land transaction in America? |

Categories

All

Archives

February 2020

|

- Guided Tours

- Self Guide Smartphone Tour

-

Revere Bells Index

- The Stickney Revere Bell Listings of 1976

- Ashby Mass. Revere Bell

- Paul Revere Bell of Beverly

- Revere Bells in Boston >

- California's 2 Paul Revere Bells

- Paul Revere & Son's Bell Westborough Massachusetts

- Falmouth, Massachusetts

- Revere Bell Fredericksburg VA

- Revere Bell Hampton NH

- First Parish Church of Kennebunk

- Revere Bells in Maine

- Revere Bell in Mansfield

- Revere Bell of Michigan

- Revere Salem Mass Bell

- Roxbury First Unitariarn Universalist Church and their Revere Bell

- Revere & Son Bell, Savannah Georgia

- Singapore Revere Bell

- Tuscaloosa Bell >

- Revere Bells Lost in Time

- Revere Bells Washington DC

- Revere Bell in Wakefield, Mass

- Revere Bells Woodstock VT

-

Bostonians

- Edward F Alexander of The Harvard 20th Civil War Regiment

- Polly Baker

- John Wilkes Booth

- The Mad Hatter, Thomas, Boston Corbett who Killed John Wilkes Booth

- Richard-Henry-Dana-Jr

- James Franklin

- Benjamin Harris of Publick Occurrences

- Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr.

- William Lloyd Garrison

- USS Thomas Hudner DDG116

- Edward Hutchinson Robbins Revere

- Amos Lincoln

- King Philip

- Mayor's of Boston

- Mum Bett & Theodore Sedgwick

- James Otis

- Paul Joseph Revere

- Reverend Larkin's Horse

- John Rowe >

- Be Proud to be Called a Lucy Stoner

- Rachel Wall , Pirate

- Paul Revere the Coroner of Boston

- Deborah Sampson

- Who was Mrs. Silence Dogood?

- Dr. Joseph Warren's Dedication

- History Blog

- Lilja's of Natick

-

Collage of Boston

- 4th of July Parade, Bristol RI

- Boston Harbor

- The Customs House

- Forest Hills Cemetery

- Georges Island

- Nonviolent Monument to Peace - Sherborn

- The Battle Road

- Skate bike and scooter park

- Cassin Young & USS Cassin Young

- MIT

- Historic Charles River

- The Roxbury Standpipe on Fort Hill

- John & Abigail Adams National Park

- Boston's Racial History - Ante-Bellum

- New Page

RSS Feed

RSS Feed