- Guided Tours

- Self Guide Smartphone Tour

-

Revere Bells Index

- The Stickney Revere Bell Listings of 1976

- Ashby Mass. Revere Bell

- Paul Revere Bell of Beverly

- Revere Bells in Boston >

- California's 2 Paul Revere Bells

- Paul Revere & Son's Bell Westborough Massachusetts

- Falmouth, Massachusetts

- Revere Bell Fredericksburg VA

- Revere Bell Hampton NH

- First Parish Church of Kennebunk

- Revere Bells in Maine

- Revere Bell in Mansfield

- Revere Bell of Michigan

- Revere Salem Mass Bell

- Roxbury First Unitariarn Universalist Church and their Revere Bell

- Revere & Son Bell, Savannah Georgia

- Singapore Revere Bell

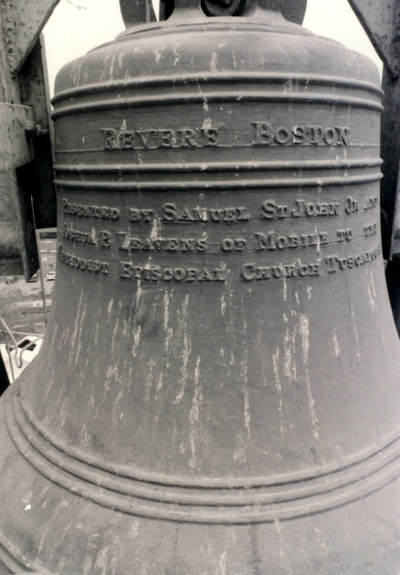

- Tuscaloosa Bell >

- Revere Bells Lost in Time

- Revere Bells Washington DC

- Revere Bell in Wakefield, Mass

- Revere Bells Woodstock VT

-

Bostonians

- Edward F Alexander of The Harvard 20th Civil War Regiment

- Polly Baker

- John Wilkes Booth

- The Mad Hatter, Thomas, Boston Corbett who Killed John Wilkes Booth

- Richard-Henry-Dana-Jr

- James Franklin

- Benjamin Harris of Publick Occurrences

- Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr.

- William Lloyd Garrison

- USS Thomas Hudner DDG116

- Edward Hutchinson Robbins Revere

- Amos Lincoln

- King Philip

- Mayor's of Boston

- Mum Bett & Theodore Sedgwick

- James Otis

- Paul Joseph Revere

- Reverend Larkin's Horse

- John Rowe >

- Be Proud to be Called a Lucy Stoner

- Rachel Wall , Pirate

- Paul Revere the Coroner of Boston

- Deborah Sampson

- Who was Mrs. Silence Dogood?

- Dr. Joseph Warren's Dedication

- History Blog

- Lilja's of Natick

-

Collage of Boston

- 4th of July Parade, Bristol RI

- Boston Harbor

- The Customs House

- Forest Hills Cemetery

- Georges Island

- Nonviolent Monument to Peace - Sherborn

- The Battle Road

- Skate bike and scooter park

- Cassin Young & USS Cassin Young

- MIT

- Historic Charles River

- The Roxbury Standpipe on Fort Hill

- John & Abigail Adams National Park

- Boston's Racial History - Ante-Bellum

- New Page

|

Richardson, born in Woburn, Massachusetts made his living as a customs official for the British Administration at Boston Harbor, Massachusetts. The local Sons of Liberty considered him a snitch. He had a privileged position. Thanks to the Writ of Assistance of 1660 the customs officials in the British Empire had a blanket court order to enter on demand any private or public structure and search for smuggled goods. Parliament offered incentives to their North American representatives to aggressively do their job. One-third of any cash converted from confiscated goods was the customs officials’ reward. The magistrate that signed the writ also received one-third and the British government the remaining third. Richardson was very competent at irritating the local Puritans beyond his money-making endeavors as a customs official. He married for money. During his marriage, he impregnated his wife’s sister. In denial, he blamed the event on their local minister. The reverend was driven out of town. Richardson’s wife died. He married her sister and charged his wife’s estate for the maintenance of her children. Richardson continued a running battle over the non-importation of British goods with the Sons of Liberty. This quote sets the scene for Richardson’s most felonious episode. “The occasion arrived on 22 February 1770, a Thursday, which, like all Thursdays, was by Boston custom a market day and a school holiday; plenty of idle schoolboys as well as numerous up-country farmers stood available to bolster the already powerful Boston mob.” Richardson worked himself into a frenzy over a non-importation sign planted on his neighbor’s house, Theophilus Lillie. The sign was the handy-craft of the Sons of Liberty and was not the first or last time a merchant’s home would be violated by a mob. Lillie’s intelligent defense of his business practice is available at Boston 1775, linked here. As the evening progressed Richardson attempted to remove the sign using another vendor’s horse and wagon as a battering ram. He failed. Richardson was now amongst the crowd and clearly more a target than Lillie. As verbal abuse was given and taken, Richardson’s windows seemed to attract any and all available stones and oyster shells lying in the road. Too many adolescents leaned on his fence and gate until it collapsed. Eventually, his wife was hit by a projectile launched by Richardson and returned by the Sons of Liberty. He had enough. Richardson rushed into his house, not to escape the crowd but to get his blunderbuss on the second floor. He pointed it out the window and fired. Poor Christopher Seider, a German immigrant of a few months, reached down to find a small object and was hit with eleven pellets from Richardson’s gun. Despite the aid of every Boston doctor, Seider, aged eleven, died a few hours later in his mother’s arms. Christopher Seider’s story is linked here. Richardson was nearly lynched but William Molineaux, perhaps the instigator of this non-importation riot, rushed him to jail with momentum provided by a raging crowd. He was tried and found guilty of murder in the first degree. The judge delayed sentencing expecting, and months later receiving, a pardon from Parliament. Richardson rushed off to the customs office in Philadelphia and continued to build on his substantial reputation. [1] http://www.masshist.org/publications/adams-papers/index.php/view/LJA02d086 Bibliography Zobel, Hiller B. The Boston massacre. New York, W.W. Norton, 1970. http://boston1775.blogspot.com/search/label/Ebenezer%20Richardson https://www.masshist.org/database/318 The Boston Gazette 3/5/1770 http://www.masshist.org/publications/adams-papers/index.php/view/LJA02d086

0 Comments

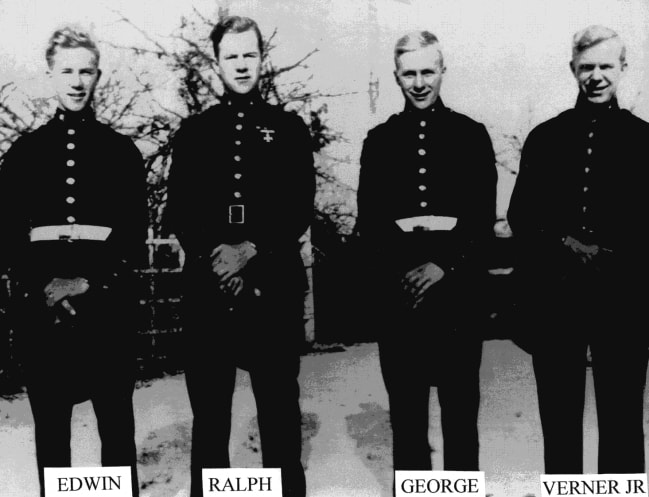

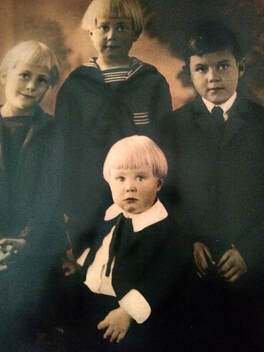

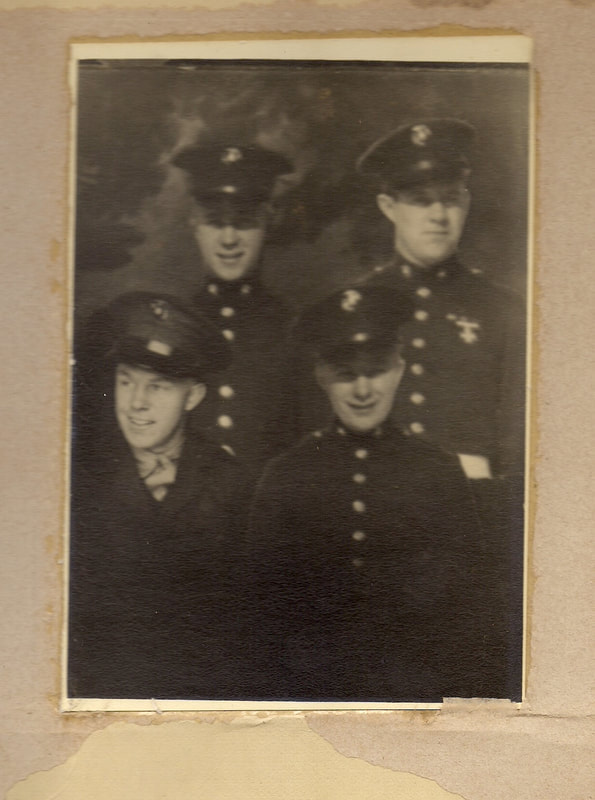

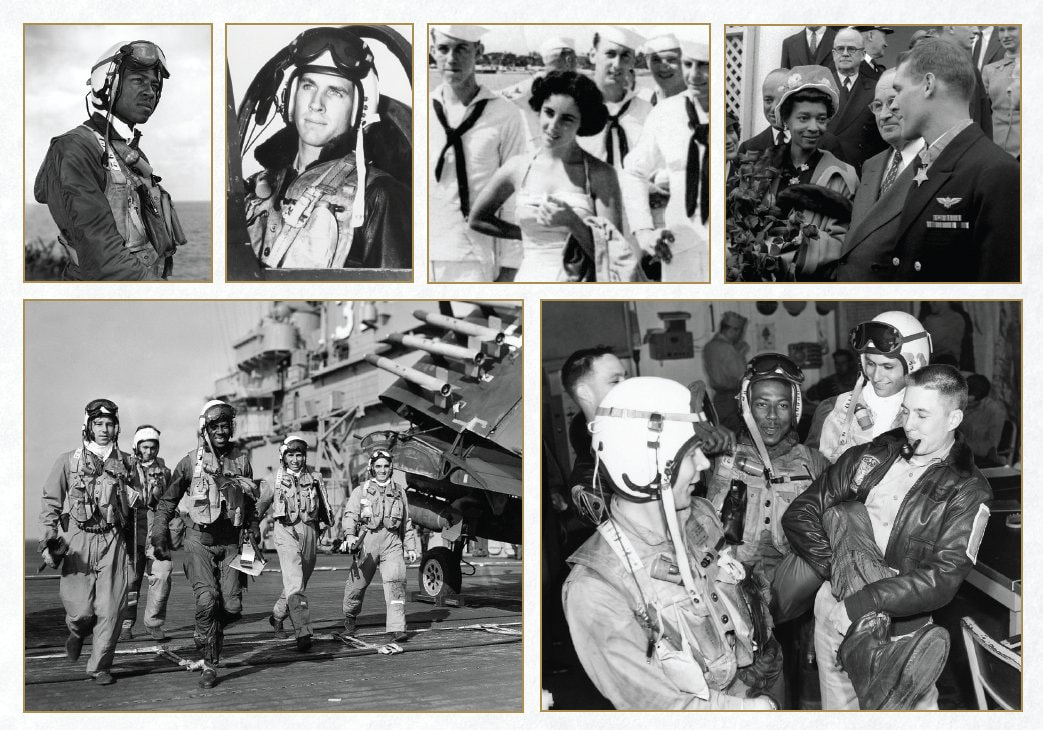

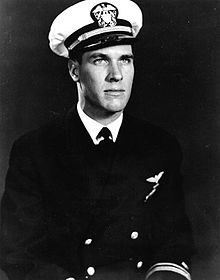

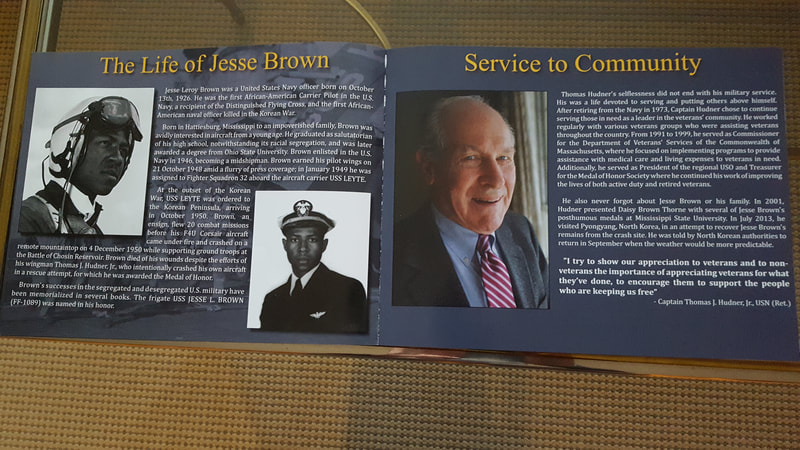

THE FOUR LILJA BROTHERS OF NATICK MASS THAT SERVED WITH THE MARINES IN THE PACIFIC DURING WWII Introduction My sons and I needed a two story high brick wall for our batters box and a long field to begin our annual stickball game. This year the elementary school on Bacon Street in Natick became our home-field. I chased our last surviving ball to the front of the school near the monument that honored the four Lilja brothers of WWII. My sons were anxious to finish the game but I drew them closer to the monument. They understood how anachronistic I can be and asked a few relevant questions. I had none of the answers. I was going to lose sleep over this until I learned more about the Liljas. This freelance blogger has many moments like this. I pursue local heroic Baystaters that the media has under-reported. The story of the Lilja Brothers of WWII that follows is one that could easily have been a classic American movie. In time, we shall report on the other set of sixteen Natick brothers that fought in this nation's wars. My inquiries began with Paul Carew, Director of Veterans Services, Natick, Ma. He provided me with a wealth of information on the town’s veterans from wars of the 20th and 21st centuries. The Town of Natick left nothing on the table. There are over 52 squares and 5 major monuments to those that served. The credit for the concentrated chronological look of the Lilja brothers was principally provided by George ( Lucky) Lilja son of Verner Jr. and Effie Hall, cousin to the brothers. They have provided a very personal look in the genealogy linked below. The Brothers at Arms from the Town of Natick Steven Spielberg produced the movie, "Private Ryan" loosely based on the true story of the Niland brothers, of Tonawanda New York, that served in WWII. All four brothers were in active combat on D-Day. Two brothers died at Normandy and third brother was captured in Burma after parachuting from a disabled B-24. Private Ryan was symbolic of many communities and families with multiple sons lost or wounded during WWII. Unfortunately, sons serving in the same war, theater or military unit are not new to US history. Joseph Warren Revere, the eleventh child of Paul Revere, lost two of his sons in the Civil War. Similar losses occurred during WWI, including the Souls twins and their three brothers. The six of seven Smith brothers were lost to Australia during WWI. Too many Gold Star Mothers suffered the loss of more than one son in WWII though only one in sixteen serving in the U.S. military, engaged in real combat. Unfortunately in war, "All gave some and some gave all."(1) Every town on either side of a conflict has a Private Ryan story. The Town of Natick sent many family members to war as blood brothers in arms, often in the same regiment. Fifty-two from this town of 14,000, during WWI and WWII, were killed in combat. Patriotism and volunteerism was the undying story behind each of them. The brothers below and many other individual soldiers of Natick are memorialized through town squares in their honor. Below is a list of those Natick families that sent two or more sons to war. The eight Intinarelli brothers, Carlos (KIA Battle of the Bugle), 7 survived including Richard that fought fifty miles away in the same battle. Six of the seven Arena brothers served in WWII; the youngest was wounded in Korea. The Seven Franciose brothers served from WWII to Vietnam. Six Arthur brothers served from WWII to Korea. All five Morris brothers served in WWII. The five Sheas including Esther, the first WAC was honored by the Town of Natick. Five Sinclairs spanning WWII, Vietnam, and Iraq. Five White brothers that served in WWII. Five Grassey brothers served in WWII, one did not come home. Four Hall Brothers. Four of five Grupposo brothers served in WWII and Anthony served in Korea. Four Barber brothers served in WWII and a fifth in Korea. Four Ordway brothers all fought in WWII. Both Casey brothers served in WWII. Vito Cadellicchio was KIA in WWII and his two brothers served in Korea. Both Gay brothers of Natick were KIA in France and a brother-in-law KIA in Germany. The Hadlick brothers served in many combat locations. Each of the four Liljas that served in WWII were born in America in the first quarter of the 20th Century. A brief genealogy back to Sweden is linked with their family tree and a collage of WWII and family images. The Liljas represent a classic look at a family devoted to America and each other. A fifth son, Robert, nine years old at the start of WWII, fought with his brother, Edwin, in Korea. There was no exemption sought by any Lilja: they all volunteered to serve. By clicking on the link below you will be taken to a page devoted to; Military History: Genealogy: Family Tree Family Album Historical Family Documents back to Sweden Effie Hall's reflection on her four cousins - scroll to the bottom Memorials Reference documents Each additional page has a collage of photos related to the Lilja family. Hover your mouse over the photo to display any additional captions and click on the photo to expand it and continue in a slide show format. Notes (1) From a song by Billy Ray Cyrus 1989 (2) The above linked website is part of the Eagle Scout project of Ben Jennings, a member of Natick’s Troop 1775. Please write to Mitch Lapin [email protected] with additional information, corrections or images. Edited by Nancy Dlott, retired reference librarian! Continuing Member Massachusetts Historical Society During the first year of the Korean War, Lieutenant Thomas J. Hudner of Fall River, Massachusetts and Ensign Jesse Brown of Hattiesburg, Mississippi were U.S. Navy pilots assigned to the aircraft carrier Leyte. They were wingmen of the VF32nd squadron, flight K from the first day of its formation. Much of their flight training happened in Quonset, Rhode Island. Jesse Brown, his wife Daisy and daughter Pam lived near the base, bringing both of their families in close contact, resulting in a deep friendship.

Tom’s father was a successful owner of a supermarket chain during Fall River’s revival after World War II. Jesse’s father did assembly line work that twice led to lay-offs in Mississippi factory towns. As a result he settled in Lux Mississippi as a sharecropper. The two wing men rose to manhood from completely different levels of society. Yet the two flyers developed similar ethical views of the world. Jesse experienced racism on a daily basis. Tom, experienced America’s subtle form of caste system, trying to be average in a town that was conflicted by budding blue collar prejudice. Both boys fought back against the system in their own way. Jesse read a biography about Jackie Robinson. He never bent to southern prejudice and never raised his hand to strike back. Tom had to defend a weaker friend from the local Portuguese bullies, outnumbered on several occasions and with little support from his Anglo-Saxon friends. By high school graduation the people in each town came to admire the maturity of the two men. The Navy’s path to integration generally mirrored the other military services though out of necessity, for want of sailors it came far sooner than the Army. Early in this nation’s history slaves used the sea to escape and avoid slave hunters. Crispus Attucks, a self- emancipated slave, sailed for twenty years under the name of Michael Johnson, to avoid capture. He was an African American and the very first of five killed during the Boston Massacre. Frederick Douglass escaped slavery in Virginia by borrowing a navy uniform and Seaman's Protection Certificate, documenting that he was a sailor and a citizen of the U.S.[i] At the Battle of Lake Erie, during the War of 1812, African Americans made up one-quarter of the personnel in the nine ships engaged against the British. Early records by the Secretary of the Navy concluded that one-fourth or 29,511 African Americans served in the navy during the Civil War. More recent numbers, based on statistical surveys by Howard University, The Department of the Navy and the National Park Service concluded that eighteen-thousand African Americans served in the Navy.[ii] Most WWII ships at sea were serviced by non-commissioned African Americans. In his non-combatant roll Doris (Dorie) Miller, an African American Navy Launderer, received the Navy Cross, Navy Distinguished Service Medal and Medal of Honor, for his defense of the USS West Virginia during the Japanese surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, December 7, 1941. A few African Americans with WWII experience became naval officers during the Korean War. In contrast, The United States Army abided by a 1792 law that restricted enlistment by African Americans until President Truman’s desegregation order of 1948. The first ever navy aviator to graduate under this new order was Jesse Brown receiving his wings on October 21, 1948. Tom graduated from the United States Naval Academy and Jesse from the Ohio State University. Soon after, Tom Hudner and Jesse Brown were trained to fly as a team at the Quonset Point Naval Air Station in the spring of 1950. Jesse was married, Tom was searching. The Korean War had not begun. Their first port of call was Nice, France, on the Riviera. Elizabeth Taylor, the decade’s hottest starlet, was in Cannes for the film festival. While sun bathing on the beach she was approached by one of Leyte’s marines on liberty. She responded positively and that led to a cohort of more marines engaged in a typical friendly star gazed discussion. She invited them to a 4:00 o’clock tea at her hotel. Tom and Jesse had no knowledge that the Marines from the Leyte had such a lucky moment. Jesse and Tom happened to walked into to the same hotel and sat down for a drink, feeling awkward in such a sophisticated environment. Both flyers were stumbling over a four o’clock refreshment when Elizabeth Taylor walked up to their table. Just a bit of good luck for the flyers. They would meet Elizabeth again that night at the casino, she would visit their ship later in the week. The rules of engagement in Korea were far too well defined. If a flyer was shot down his wingman was not to attempt any rescue that would jeopardize another plane or pilot. The penalty was a court-martial. It appeared that a single rifle shot hit Jesse’s oil line on the fourth day of flying air cover for the Marines surrounded by the Chinese at the Chosin Reservoir. Jesse’s engine was about to fail. He had little choice but to crash land his plane near a mountain top seventeen miles from the nearest Marine base at Hagaru-ri, North Korea. The snow on the mountain hid the moon-like craters and rocks as Jesse crash landed. His plane broke in half trapping his legs under the cockpit. Tom Hudner circled above waiting for Jesse to exit the crashed Corsair. Jesse managed a wave. Minutes later Tom understood that Jesse could not exit the plane on his own. A fire ignited in the fuselage. Tom and Jesse and the four other Corsair pilots circling above, understood the Navy’s position on downed pilots. Nonetheless, Tom Hudner chose to crash land his plane close to Jesse. His plane sustained far less damage but was equally inoperable. As a result a helicopter was dispatched to rescue the pilots. Tom and Jesse were suffering in minus 30 Fahrenheit temperatures. Attempts to remove Jesse from the plane failed. Jesse’s breathing was shallow and erratic. His lips were blue and his skin glazed. With the help of a fireman’s ax and the copter pilot, Jesse could not be freed. As evening set in the helicopter pilot prompted Tom to return with him to base. The copter was not equipped for night flying among mountains that reached above three-thousand five hundred feet and in thin air that reduced the lift of the helicopter blades. Under the trying circumstances Charlie Ward was the only volunteer to come to their aid. As Charlie and Tom walked back to Jesse's plane it was clear that he had perished. Despite numerous efforts they could not free Jesse’s body from the Corsair. Tom returned with the copter to the Leyte a hundred miles from the crash site. He was escorted into the flight room expecting to learn of his court-martial. Instead he was treated as a hero. The next day the ship’s captain, the senior most officer on the carrier, consulted with Tom on Jesse’s remains. Of equal concern was the secret electronic equipment on the Corsair. Tom responded that Jesse would not want another flyer or plane lost in the effort to remove his remains. Tom recalled the hundreds of Chinese in white parkas moving to the crest of the mountain as they made their escape. The captain proceeded to ask if the Leyte should give Jesse a proper burial. Under the circumstances this meant a fly over, recitation of the Lord’s Prayer and the dropping of napalm to seal off the plane and Jesse’s remains. Tom would not accompany the four Corsairs that partook in Jesse’s funeral. On the day of the funeral the pilots noticed that Jesse’s flight clothes had been removed. They gave Jesse the classic fighter send-0ff for a downed pilot behind enemy lines. Three months later the Leyte returned to San Diego for refitting. Elizabeth Taylor was in town and suggested to the Leyte’s captain that she would like to visit with the crew. After some consideration Captain Sisson politely advised Liz that having lost three sailors during this cruise her visit might not be appropriate. In the spring of 1951, Jesse’s last letter to Daisy arrived. It had been mis-directed to a relative. Jesse wrote it the night before his death. The letter is available online. It is four pages of loving thoughts to Daisy and might easily rate as one of the most heart-felt goodbyes. Here is a brief sample; I have to fly tomorrow. But so far as that goes my heart hasn’t been down to earth since the first time you kissed me, and when you love me you “send” it clear out-of-this-world. Listen to or read the full four pages at this location; Devotion: An Epic Story of Heroism, Friendship, and Sacrifice, Adam Makos, Ballantine Books, New York. Also available on CD at most libraries. CD11 Weeks after the Leyte’s return to the United States, Tom received a phone call from the Pentagon and was ordered to the White House to receive the Medal of Honor. Up to this point most publications of Tom and Jesse’s exploits were often slanted by racial preconceptions. Jesse’s wife, Daisy, was asked to attend the White House ceremony. She had not spoken to Tom since the day the Leyte launched for the Mediterranean. The newspaper articles led her to believe that Jesse’s remains were missing. After the ceremony Tom and Daisy met in the White House and for the first time released their emotions. Tom corrected the entire history of that decisive day, explaining to Daisy that a proper funeral took place and the location of the aircraft was documented. He did not hold back the details of the naval funeral. All of this was positively received by Daisy. While Jesse’s last moments were full of gruesome details Daisy was pleased that Jesse did not die alone as implied by many second hand reports. She left with the hope that someday his remains could be properly interred in Arlington National Cemetery. Unfortunately, as of now Jesse’s remains have not been returned to the family. Tom Hudner remained a close friend of Daisy and her daughter Pam until his death. Later in life, Daisy thoroughly briefed Pam on Jesse’s death and provided her with implicit instructions if Jesse’s remains were released by the North Koreans. In 2013 Tom was successful at arranging a trip to North Korea to seek Jesse’s remains. He met with several generals of the North Korean military but returned home with no real assurances. Tom died on November 18, 2017, and to this day Jesse’s remains most certainly are in the hands of the North Koreans. Post Script;

Bibliography

[i] http://www.americaslibrary.gov/aa/douglass/aa_douglass_escape_3.html [ii] https://www.nps.gov/civilwar/soldiers-and-sailors-database.htm John Brown’s Harper Ferry Armory raid, October 16-18th, 1859, was 2 years in planning with Boston’s Secret Six. He was the madman; they were the Brahmins. Two ministers, an educator, a physician educator of the blind and two successful businessmen. https://www.walkbostonhistory.com/apps/search?q=secret+six Figure 1;The Secret Six From left to right, Gerrit Smith, Samuel Gridley Howe, George Luther Stearn, Theodore Parker (Bald), Thomas Wentworth Higginson & Franklin Sanborn. Collage attributed to UMKC Law.

Both ministers were prone to violence. Read more of Higginson’s defiance of the law and military service during the Civil War and of Theodore Parker’s direct involvement in the Fugitive Slave Riots. For a bio of all six men click here. Endnote: [1] John Brown’s Body Lies A-Mouldering in the Grave, by Julia Ward Howe, wife of Samuel Gridley Howe of the Secret Six. Julia used the musical score from “The Battle Hymn of the Republic.” John Brown is buried in North Elba, N.Y., near Lake Placid. The Revere Family Bell of 1828, Donated by Messrs.’., Leavens and

St John Jr, to the Methodist Church in Tuscaloosa, Alabama Abridged Genealogy: Joshua Bayley Leavens and Samuel St. John Jr, were intimately involved in procuring the Revere Bell for the First Methodist Episcopal Church of Tuscaloosa. Joshua Leavens was born in Reading, Vermont, and Samuel St John Jr in New Canaan, Connecticut. John Leavens (Levens, Levins, Levinz or Levnze) first arrived in 1632 and settled in Roxbury, Massachusetts. The first time that the Leavens and St John families brushed elbows was in 1634 with the immigration of Mathias St John to Dorchester, Massachusetts. Both villages were separate chartered towns free of Boston’s Puritan dominance. Today, they are neighborhoods on the southeast side of Boston. The first suggestion that the donors crossed paths was the War of 1812. Each volunteered and fought in a New York Militia unit. Both units served at the 1814 Battle of Plattsburgh, New York. We cannot yet confirm the reasons that Leavens and St John volunteered for the New York Militia versus a Connecticut or Vermont unit. Our Endnote [1] speculates on the reason. Samuel St John’s first partner, Edward Griffith, died in the year 1824 in New York City. Joshua Leavens joined the establishment of St John Jr in 1825. Their partnership began in New York City, and by 1828 they had opened operations in Mobile, Alabama. We have tracked their business and legal activity by newspaper announcements made in various regional papers. We have posted them in the image section at the end of this report https://www.walkbostonhistory.com/tuscaloosa-bell.html. The clippings provide insight into a sophisticated legal and business environment. In our full blog we identified the two bell donors from their youth to their death. Additionally, we have provided a genealogy of both families back to 1632 and 1634. Follow the donors from the War of 1812 to Leavens passing in Mobile Alabama and St. John Jr’s., last days in New Haven Connecticut in 1866. https://www.walkbostonhistory.com/tuscaloosa-bell.html. Images of the bell foundry then and now are provided along with the Revere ledger documenting the initial date of purchase and completion. [1] There may be a historical answer. The British invaded from Canada via the upstate New York waterway of Lake Champlain to split New England from the rest of the United States. The waterway runs for miles abutting New York State on its western side and Vermont to its east. The Governors of Vermont, Connecticut, and Massachusetts did not commit their militias to defend New York. Contentiously, all three governors believed they were chartered to use the militia only to defend their state. In truth, New England was lukewarm on the war as the prominent issue of “impressment” had been resolved in writing before the beginning of combat. Additionally, local commerce with England was substantial. Thirteen years later, the United States Supreme Court overturned the Governors’ opinions. Under the circumstances, volunteers made their way to New York to serve in the war. https://www.walkbostonhistory.com/tuscaloosa-bell.html from 1632 to 2018. www.walkbostonhistory.com/revere-bells-index.html for more on the Revere Bells. Benjamin Harris was born in London in 1673, and immigrated to New England in 1686, leaving his family behind. He eventually returned to London and died in 1716. He was thoroughly anti-Catholic throughout his life.

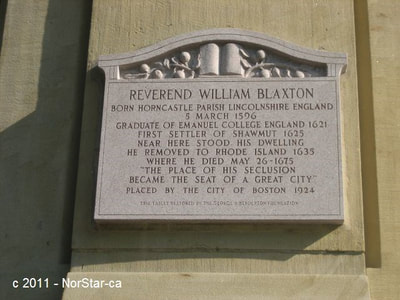

His most notable publication The New England Primer, used in every school, made him socially influential. With particularity, Harris attempted to publish Boston's first newspaper on September 25th, 1690, sixty years and two months after the Puritans arrived in Salem. The Publick Occurrence . . . may well have been a most innovative publication. Here is one example; the fourth page was left blank so the readers could write their personal “news” or views before they passed the paper to neighbors. Wouldn't this be fun or scandalous today?? The initial publication detailed suicides, several hostile Indian events, health matters like small-pox, fires, citizens suffering depression, and continued to debauch the French monarch's incestual sleeping habit. Yet, one of his promises in the first and only edition was “towards the Curing, or at least the Charming of that Spirit of Lying, which prevails amongst us.” Unfortunately, four days after the first edition, September 28, 1690, the "Governour Council" shut down the paper, based on "doubtful and uncertain Reports." Harris was the first to lose the initiative. By 1800, over thirty-nine newspapers began and collapsed in Boston. A handful survived into the 19th Century. It was a very risky business. References; By rough count The Boston Public Library, microfilm records had at least 39 different newspapers for the period. I had to give up counting. Here's a tabulation; https://www.colonialsociety.org/publications/301/list-boston-newspapers-years-1704-1780 Massachusetts Historical Society, collection https://www.masshist.org/search?terms=newspapers&start=40&num=10 tracks many of the most influential and enduring papers. Reverend William Braxton

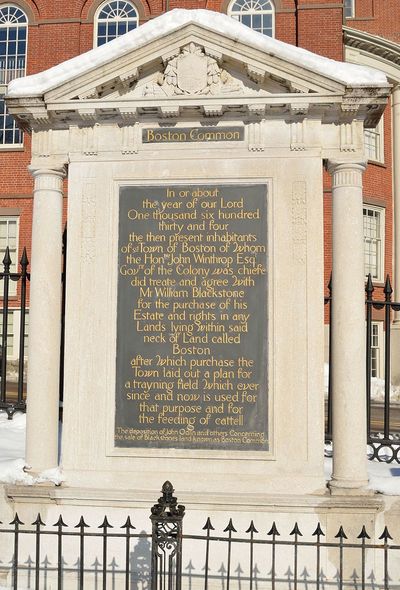

1595-1675 The Reverend arrived in Weymouth, Massachusetts with the Robert Gorges expedition with the notion that the Plimoth Plantation was able and willing to support them for a fee. Unfortunately, the additional one-hundred Gorges further divided the Plantations meager winter rations. Fortunately, the survivors of the Gorges realized they had made a poor investment and by 1625, all but the Reverend returned to England. William Bradford, Governor of the Plimoth Plantation was relieved, as the Gorges were not particularly diplomatic to the native Wampanoag. The Indians were vital to the plantations survival. The Reverend migrated to an area we refer to as the Boston Common. The Shawmut, a segment of the Massachusetts Native Americans, became his friend and helped him find water. There were five natural springs, Mill Creek and the Charles River to support life. He cultivated six acres of land to support him, sharing his produce with the Shawmut. Unlucky for the Reverend, On September 17, 1630, he was engaged by the advance party of the Puritans of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Reverend Braxton was an Episcopalian minister. He supported the Church of England. The Puritans that immigrated to Salem, Massachusetts believed the Church of England was influenced by the Pope. They wanted to restore Christianity to the scriptures and set an example for England to shed its sinful ways. Prompted by The Puritan Way, Reverend Braxton quickly learned that he was his own best company. In negotiations with John Winthrop and the Massachusetts Bay Colony, he sold the fifty acres that became the Boston Common and moved to Blackstone Valley. As so often happened in New England, someone registered the name incorrectly. It should have been the Braxton Valley. To this day this error has been perpetuated. He was not entirely forgotten. Two plaques on Beacon Street, across from the Boston Common, mark his impact on the area. Above is the 1924 and most recently dedicated plaque at the corner of Tremont and Union Street. The error has been perpetuated. In a light hearted sense Reverend Braxton really did not have a title or a charter to the 50 acres of the Boston Common. Could this have been the first fraudulent land transaction in America? |

Categories

All

Archives

February 2020

|

- Guided Tours

- Self Guide Smartphone Tour

-

Revere Bells Index

- The Stickney Revere Bell Listings of 1976

- Ashby Mass. Revere Bell

- Paul Revere Bell of Beverly

- Revere Bells in Boston >

- California's 2 Paul Revere Bells

- Paul Revere & Son's Bell Westborough Massachusetts

- Falmouth, Massachusetts

- Revere Bell Fredericksburg VA

- Revere Bell Hampton NH

- First Parish Church of Kennebunk

- Revere Bells in Maine

- Revere Bell in Mansfield

- Revere Bell of Michigan

- Revere Salem Mass Bell

- Roxbury First Unitariarn Universalist Church and their Revere Bell

- Revere & Son Bell, Savannah Georgia

- Singapore Revere Bell

- Tuscaloosa Bell >

- Revere Bells Lost in Time

- Revere Bells Washington DC

- Revere Bell in Wakefield, Mass

- Revere Bells Woodstock VT

-

Bostonians

- Edward F Alexander of The Harvard 20th Civil War Regiment

- Polly Baker

- John Wilkes Booth

- The Mad Hatter, Thomas, Boston Corbett who Killed John Wilkes Booth

- Richard-Henry-Dana-Jr

- James Franklin

- Benjamin Harris of Publick Occurrences

- Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr.

- William Lloyd Garrison

- USS Thomas Hudner DDG116

- Edward Hutchinson Robbins Revere

- Amos Lincoln

- King Philip

- Mayor's of Boston

- Mum Bett & Theodore Sedgwick

- James Otis

- Paul Joseph Revere

- Reverend Larkin's Horse

- John Rowe >

- Be Proud to be Called a Lucy Stoner

- Rachel Wall , Pirate

- Paul Revere the Coroner of Boston

- Deborah Sampson

- Who was Mrs. Silence Dogood?

- Dr. Joseph Warren's Dedication

- History Blog

- Lilja's of Natick

-

Collage of Boston

- 4th of July Parade, Bristol RI

- Boston Harbor

- The Customs House

- Forest Hills Cemetery

- Georges Island

- Nonviolent Monument to Peace - Sherborn

- The Battle Road

- Skate bike and scooter park

- Cassin Young & USS Cassin Young

- MIT

- Historic Charles River

- The Roxbury Standpipe on Fort Hill

- John & Abigail Adams National Park

- Boston's Racial History - Ante-Bellum

- New Page

RSS Feed

RSS Feed