- Guided Tours

- Self Guide Smartphone Tour

-

Revere Bells Index

- The Stickney Revere Bell Listings of 1976

- Ashby Mass. Revere Bell

- Paul Revere Bell of Beverly

- Revere Bells in Boston >

- California's 2 Paul Revere Bells

- Paul Revere & Son's Bell Westborough Massachusetts

- Falmouth, Massachusetts

- Revere Bell Fredericksburg VA

- Revere Bell Hampton NH

- First Parish Church of Kennebunk

- Revere Bells in Maine

- Revere Bell in Mansfield

- Revere Bell of Michigan

- Revere Salem Mass Bell

- Roxbury First Unitariarn Universalist Church and their Revere Bell

- Revere & Son Bell, Savannah Georgia

- Singapore Revere Bell

- Tuscaloosa Bell >

- Revere Bells Lost in Time

- Revere Bells Washington DC

- Revere Bell in Wakefield, Mass

- Revere Bells Woodstock VT

-

Bostonians

- Edward F Alexander of The Harvard 20th Civil War Regiment

- Polly Baker

- John Wilkes Booth

- The Mad Hatter, Thomas, Boston Corbett who Killed John Wilkes Booth

- Richard-Henry-Dana-Jr

- James Franklin

- Benjamin Harris of Publick Occurrences

- Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr.

- William Lloyd Garrison

- USS Thomas Hudner DDG116

- Edward Hutchinson Robbins Revere

- Amos Lincoln

- King Philip

- Mayor's of Boston

- Mum Bett & Theodore Sedgwick

- James Otis

- Paul Joseph Revere

- Reverend Larkin's Horse

- John Rowe >

- Be Proud to be Called a Lucy Stoner

- Rachel Wall , Pirate

- Paul Revere the Coroner of Boston

- Deborah Sampson

- Who was Mrs. Silence Dogood?

- Dr. Joseph Warren's Dedication

- History Blog

- Lilja's of Natick

-

Collage of Boston

- 4th of July Parade, Bristol RI

- Boston Harbor

- The Customs House

- Forest Hills Cemetery

- Georges Island

- Nonviolent Monument to Peace - Sherborn

- The Battle Road

- Skate bike and scooter park

- Cassin Young & USS Cassin Young

- MIT

- Historic Charles River

- The Roxbury Standpipe on Fort Hill

- John & Abigail Adams National Park

- Boston's Racial History - Ante-Bellum

- New Page

Fifth of Six Articles about those that Financed John Brown - Samuel Gridley Howe

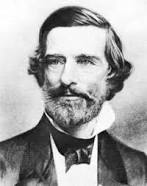

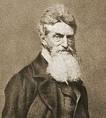

As he graduated medical school slavery was just becoming the burning issue of the land. The actual attention getter in the news was the Greek Revolt against the Ottoman Empire. It was the latest revolutionary domino to fall in the Balkans. Samuel Gridley Howe lost no time after graduation from medical school, to volunteer as a surgeon for the Greek revolutionary cause. At the end of his service to Greece, he moved to Prussia to study education for the blind. While in Berlin, General Lafayette asked him to extend his tour to the Vistula, a large area and river in Poland. Unfortunately, this inadvertently engaged him in European politics. He was ordered to return to Berlin and subsequently arrested. His internment lasted five weeks. [i] In 1832, upon his return from prison in Prussia, he set out to establish a school to educate the blind. [ii] His plan was unique as it sought to educate blind students through their other senses. Sam’s first students were two Andover, MA girls from the Carter family that had five blind children. By 1842, Howe founded the Perkins School for the Blind, originally in his home on Pearl Street, Boston. Thomas Handasyd Perkins assisted him financially with the incorporation of the school and served as a trustee. Howe successfully achieved an international first by educating deaf and blind Laura Bridgman to read and write in braille. This took place fifty years before Helen Keller achieved fame at the Perkins School. His writings on the subject were published by European journals and read by thousands. The school’s international reputation was enhanced by a visit from Charles Dickens. Dickens met with Bridgman and then endorsed the school in his “American Notes”, a travelogue of his two year visit to America: a good bit of it spent at the Parker House in Boston. Later in the century the school would be the center of innovative teaching thanks to Howe, Ann Sullivan and her student Helen Keller.[iii] For now, in 1842, Samuel Gridley Howe was world renown. The school and Bridgman became a tourist attraction.[iv] In 1843 Howe attempted to convince Congress to fund a national library for the blind but his efforts failed. In reaction, he decided to run for Congress as a Whig, and work for funding for the blind as a Congressman. Unfortunately, he lost the election of 1846. With the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, made possible by Daniel Webster’s compromise with the “Cotton Whigs”, Howe’s politics radicalized. This act permitted slave chasers to cross the Mason Dixon Line and return any self-emancipated slaves to their owners. Boston became a target of the slave chasers as it had a large runaway slave population. In resistance to this activity, Howe joined the Boston Vigilance Committee with William Lloyd Garrison, Charles Sumner, Theodore Parker, William Cooper Nell, Lewis Hayden, George Luther Stearns and Franklin Sanborn and many others. The Committee was formed to address slavery, particularly in “Bloody Kansas.” Between 1851 and 1854, Boston experienced three riots that brought the Committee, slave catchers and the Federal and State governments into physical confrontations. Several Committee members and The Secret Six crossed the line of non-violence in their opposition to the Fugitive Slave Act. Many historians, then and now, have suggested that Dr. Howe was a principle activist in all three slave catcher riots in Boston. Eyewitness testimony can often be contradictory. In any case Dr. Howe appears to have rushed the Federal Court House in Boston in 1854, with hundreds of other abolitionists, attempting to free Anthony Burns. A U.S. marshall was killed in the ensuing battle. Perhaps it is best left that Dr. Howe was an activist. To this day the individual that shot at and subsequently stabbed the marshall, has remained unknown. The attention given Boston, on both sides of the slavery issue, clearly alerted John Brown to an abolitionist center of support that just might adopt his plan for a slave uprising. Inversely, those called The Secret Six could not help but hear of Captain John Brown’s exploits in “Bloody Kansas” through their committee activity and visits to Kansas. Unfortunately, one side of the Mason Dixon line would call him an abolitionist and the other a first degree murderer. Hill Peebles Wilson, in his book, “John Brown Soldier of Fortune” [v], suggested that the scent of easy money attracted John Brown to the Secret Six. John Brown seemed to create a degree of credibility by proposing a bill to the Massachusetts Legislature in 1857,to fund $100,000, in defense of free Kansas.[vi] The bill was not funded despite John Brown’s personal appearance in front of the committee. Shortly, John Brown met with Franklin Sanborn, Treasurer of the Massachusetts State Kansas Committee. Armed with reference letters from several Midwest governors, Brown was able to establish his credentials in the fight against slavery. His historical indictment, as a murderer, was not yet known publicly. Sanborn, the youngest of The Secret Six, introduced Brown to numerous abolitionists and transcendentalists in Boston including Dr. Howe. Julia Ward Howe recollected that her husband greatly admired John Brown for his commitment to end slavery. In her own hand, she writes that “Sometime in the fifties my husband spoke to me of a very remarkable man, of whom, he said, seemed intent to devote his life to the redemption of the coloured race from slavery. . . .” One year later in 1858, John Brown was a guest of the Howes in their South Boston home. [vii] Dr. Howe’s son suggested that midway through 1858, The Secret Six were surprised but finally understood the extent of John Brown’s raid. Apparently, Dr. Howe withdrew his support. Yet, Julia suggests that well into 1859, Dr. Howe was providing written references for John Brown to other abolitionists that might financially support his enterprise. There clearly was a bond between the two men of similar age, height, build, temperament and religious orientation reflected in their appearance.[8] The raid failed. Dr. Howe’s name surfaced early as a conspirator in the New York papers. His immediate response was to publish a “card” emphasizing John Brown’s independence of thought and action, disavowing knowledge of the violence of the plan, denigrating those that suggested he supported Brown and expressing his admiration for John Brown’s “nobility”. At this point John Brown was convicted of treason and murder but not yet hanged. Soon Dr. Howe chose discretion over valor. To avoid a possible indictment, he left for a vacation in Montreal, Canada. Although, in one letter he referred to his vacation as an expatriation. The aftermath of John Brown’s Raid triggered intense debate. Congressional hearings, newspapers, and politicians from the South incriminated anyone modestly linked by abolitionist activity to the Secret Six. While the debate raged Dr. Howe, Sanborn and Stearns fled to Canada to avoid prosecution. Gerrit Smith walked into a sanitarium. Reverend Parker was in Florence, Italy before the raid suffering from tuberculosis. Higginson remained in Worcester and literally dared arrest. A year and a half later southern states began seceding from the Union. Any appetite to prosecute The Secret Six faded. Higginson enlisted, was wounded and later was appointed a colonel of a colored regiment. In 1863 Dr. Howe was appointed by the Secretary of State to a commission on slavery. U. S. Marshalls attempted to seize Franklin Sanborn for a Senate hearing. The town of Concord came out by the hundreds to physically resist the arrest. His professional life blossomed in the sciences, education for the deaf, care for orphaned children and supervision of state charities. The law never caught up with him but a railroad car ran him over in 1917. Reverend Parker died of tuberculosis in Florence, Italy shortly after John Brown’s execution. Gerrit Smith sued the Chicago Tribune that insisted he knew of John Brown’s violent intentions. Gerrit spent several weeks in an insane asylum, perhaps for security or as a defense against indictment. United States Senator Jefferson Davis, fomerly United State Secretary of War, attempted to have Smith hanged along with John Brown. Two years after the end of the war Smith supported a bond to free Jefferson Davis from prison. George Luther Stearns took primary responsibility for recruiting the all colored regiments of the 54th, 55th and the 5th Massachusetts colored cavalry regiment. Roughly speaking he recruited tens of thousands of colored soldiers. Stearns did not forget the children and families of the black regiments that were left to support themselves. He established schools for their children and lobbied the State of Massachusetts to provide welfare payments for the families of the regiments. In the end, The Secret Six supported John Brown with a fund of five-hundred dollars. This was enough to arm 28 men. Half of the Six did their best to deny an association or understanding of John Brown’s revolt. Others, such as Higginson defied arrest. Yet each of the Six continued to follow his abolitionist and existential conscience through to the end of slavery. You can find modest biographies on all in our blog under “Abolitionist.” Despite Dr. Howe’s fleeting moments, we end with a fitting poetic tribute to a complex, philanthropist, educator, abolitionist, militant, political activist, author, suffragist and physician, by Oliver Wendell Holmes (senior) pasted here in part; . . . Ere winter’s killing frosts, The message came: so passed away The friend our earth has lost[viii] P.S. Laura Bridgman, was the first person with deaf/blindness to learn to read to write. Ann Sullivan could not read or write at the age of 14, due to glaucoma, until she entered the Perkins Institution. Ann was from a poor immigrant Irish family that broke up or lost their lives in almshouses. In a few short years Ann would become a teacher at Perkins and assigned to seven- year-old death and blind, Helen Keller. Initially she would use the teaching techniques used by Samuel Howe on Laura Bridgman. The full story of the teacher- student relationship between Ann and Helen is a must read. This site on Perkins Institutes web page is a great beginning, http://www.perkins.org/history/people/anne-sullivan. Samuel Howe, Jr., wrote a two volume biography on his father, years after his mother and sister did their version. He tells very interesting stories of Dr. Howe’s bravery on page 18 and 19 of volume two. Available free on Google Scholar. Letters and Journals of Samuel Gridley Howe, Volume 2 By Samuel Gridley Howe, Franklin Benjamin Sanborn, available on Google Scholar [i] Letters and Journals of Samuel Gridley Howe, Volume 1 By Samuel Gridley Howe , Franklin Benjamin Sanborn,Google Scholar Read his personal letters on prison from page 400-418 [ii] Letters and Journals of Samuel Gridley Howe, Volume 1 By Samuel Gridley Howe , Franklin Benjamin Sanborn,Google Scholar https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=1C0AAAAAYAAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA11&dq=samuel+gridley+howe&ots=LhkcHMlnAM&sig=iZaSkWc6WA6XNPN_OZox41XYNiw#v=onepage&q=samuel%20gridley%20howe&f=false Edited by his daughter Laura E Richards Dana Esters & Company ; Colonial Press, Boston USA. [iii] Footnote on the Perkins Institute’s early years. The Schools web site. [iv]Paraphrase; Charles Dickens and Samuel Gridley Howe Gitter, Elisabeth G. Dickens Quarterly8.4 (Dec 1, 1991): 162. [v] John Brown, Soldier of Fortune, a Critique by Hill Peebbles Wilson,1913, The Cornhill Company, Boston, Harvard College Library May 24, 1942. Pages 184-245 [vi] John Brown, Soldier of Fortune, a Critique by Hill Peebbles Wilson,1913, The Cornhill Company, Boston, Harvard College Library, May 24, 1942. Pages 184 to 245. [vii] Letters and Journals of Samuel Gridley Howe, Volume 1 By Samuel Gridley Howe, Franklin Benjamin Sanborn,Google Scholar https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=1C0AAAAAYAAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA11&dq=samuel+gridley+howe&ots=LhkcHMlnAM&sig=iZaSkWc6WA6XNPN_OZox41XYNiw#v=onepage&q=samuel%20gridley%20howe&f=false pages 435 and 436 [viii] Full text of Holmes tribute to Howe pages iX to Xii. Full text in Letters and Journals of Samuel Gridley Howe, Volume 1 By Samuel Gridley Howe, Franklin Benjamin Sanborn,Google Scholar https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=1C0AAAAAYAAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA11&dq=samuel+gridley+howe&ots=LhkcHMlnAM&sig=iZaSkWc6WA6XNPN_OZox41XYNiw#v=onepage&q=samuel%20gridley%20howe&f=false [8]

1 Comment

|

Categories

All

Archives

February 2020

|

- Guided Tours

- Self Guide Smartphone Tour

-

Revere Bells Index

- The Stickney Revere Bell Listings of 1976

- Ashby Mass. Revere Bell

- Paul Revere Bell of Beverly

- Revere Bells in Boston >

- California's 2 Paul Revere Bells

- Paul Revere & Son's Bell Westborough Massachusetts

- Falmouth, Massachusetts

- Revere Bell Fredericksburg VA

- Revere Bell Hampton NH

- First Parish Church of Kennebunk

- Revere Bells in Maine

- Revere Bell in Mansfield

- Revere Bell of Michigan

- Revere Salem Mass Bell

- Roxbury First Unitariarn Universalist Church and their Revere Bell

- Revere & Son Bell, Savannah Georgia

- Singapore Revere Bell

- Tuscaloosa Bell >

- Revere Bells Lost in Time

- Revere Bells Washington DC

- Revere Bell in Wakefield, Mass

- Revere Bells Woodstock VT

-

Bostonians

- Edward F Alexander of The Harvard 20th Civil War Regiment

- Polly Baker

- John Wilkes Booth

- The Mad Hatter, Thomas, Boston Corbett who Killed John Wilkes Booth

- Richard-Henry-Dana-Jr

- James Franklin

- Benjamin Harris of Publick Occurrences

- Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr.

- William Lloyd Garrison

- USS Thomas Hudner DDG116

- Edward Hutchinson Robbins Revere

- Amos Lincoln

- King Philip

- Mayor's of Boston

- Mum Bett & Theodore Sedgwick

- James Otis

- Paul Joseph Revere

- Reverend Larkin's Horse

- John Rowe >

- Be Proud to be Called a Lucy Stoner

- Rachel Wall , Pirate

- Paul Revere the Coroner of Boston

- Deborah Sampson

- Who was Mrs. Silence Dogood?

- Dr. Joseph Warren's Dedication

- History Blog

- Lilja's of Natick

-

Collage of Boston

- 4th of July Parade, Bristol RI

- Boston Harbor

- The Customs House

- Forest Hills Cemetery

- Georges Island

- Nonviolent Monument to Peace - Sherborn

- The Battle Road

- Skate bike and scooter park

- Cassin Young & USS Cassin Young

- MIT

- Historic Charles River

- The Roxbury Standpipe on Fort Hill

- John & Abigail Adams National Park

- Boston's Racial History - Ante-Bellum

- New Page

RSS Feed

RSS Feed