- Guided Tours

- Self Guide Smartphone Tour

-

Revere Bells Index

- The Stickney Revere Bell Listings of 1976

- Ashby Mass. Revere Bell

- Paul Revere Bell of Beverly

- Revere Bells in Boston >

- California's 2 Paul Revere Bells

- Paul Revere & Son's Bell Westborough Massachusetts

- Falmouth, Massachusetts

- Revere Bell Fredericksburg VA

- Revere Bell Hampton NH

- First Parish Church of Kennebunk

- Revere Bells in Maine

- Revere Bell in Mansfield

- Revere Bell of Michigan

- Revere Salem Mass Bell

- Roxbury First Unitariarn Universalist Church and their Revere Bell

- Revere & Son Bell, Savannah Georgia

- Singapore Revere Bell

- Tuscaloosa Bell >

- Revere Bells Lost in Time

- Revere Bells Washington DC

- Revere Bell in Wakefield, Mass

- Revere Bells Woodstock VT

-

Bostonians

- Edward F Alexander of The Harvard 20th Civil War Regiment

- Polly Baker

- John Wilkes Booth

- The Mad Hatter, Thomas, Boston Corbett who Killed John Wilkes Booth

- Richard-Henry-Dana-Jr

- James Franklin

- Benjamin Harris of Publick Occurrences

- Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr.

- William Lloyd Garrison

- USS Thomas Hudner DDG116

- Edward Hutchinson Robbins Revere

- Amos Lincoln

- King Philip

- Mayor's of Boston

- Mum Bett & Theodore Sedgwick

- James Otis

- Paul Joseph Revere

- Reverend Larkin's Horse

- John Rowe >

- Be Proud to be Called a Lucy Stoner

- Rachel Wall , Pirate

- Paul Revere the Coroner of Boston

- Deborah Sampson

- Who was Mrs. Silence Dogood?

- Dr. Joseph Warren's Dedication

- History Blog

- Lilja's of Natick

-

Collage of Boston

- 4th of July Parade, Bristol RI

- Boston Harbor

- The Customs House

- Forest Hills Cemetery

- Georges Island

- Nonviolent Monument to Peace - Sherborn

- The Battle Road

- Skate bike and scooter park

- Cassin Young & USS Cassin Young

- MIT

- Historic Charles River

- The Roxbury Standpipe on Fort Hill

- John & Abigail Adams National Park

- Boston's Racial History - Ante-Bellum

- New Page

|

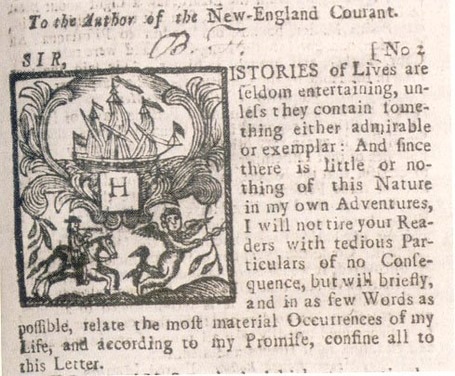

The Pseudonyms of Ben Franklin The Puritans assured the Massachusetts Bay Colony of homogeneity by insisting everyone received a public education to learn to read the Bible. Ben did not adapt well to the rigors of the nation's first public school, The Boston Latin School. He was obviously smart enough to pass the entrance exam, but his lack of discipline may well have been his downfall. Ben’s rigid Puritan father covered up this failure by claiming the family needed to invest the tuition elsewhere. Because of another false start at schooling, Ben was self-taught. The New England Courant was the Colonies first independent newspaper that also published almanacs. In 1722, in need of Puritan principles, Ben was indentured by his father, to his brother, James. James was given specific orders by his father to introduce discipline to Ben’s work ethic. James would not let Ben write for the paper. So Ben chose a female pen name and slipped fourteen different satirical letters under the printing press door, in the middle of the night, every other week. Ben chose the name Silence DoGood as a direct assault on Cotton Mather, a Puritan minister that preached the principle that silence is golden and “doing Good” is a ticket to heaven.[i] Cotton Mather wrote 450 books. Reading just one of Mather’s preachings was probably all Ben needed to pun the name Silence DoGood. Each letter covered a different topic including the church in general, drinking to excess, idle chatter, religious hypocrisy, the lack of poetry in America, free speech, education, guilt, pride, courtship and a dissertation on “night walkers,” that I best not interpret. Ben was sixteen years of age at the time. Some Bostonians understood that the author was not actually the spinster portrayed in the journals. Unfortunately for James, the Godly (as the Puritans called themselves) held him responsible. James was already scandalizing Boston with “yellow journalism” accusing the town fathers of collusion with pirates. A real issue in New England prior to the American Revolution. The anonymous writings of Silence DoGood was the “straw that broke the camel’s back.” Town officials reacted meekly since the people of Boston supported the Courant, especially while it accused officials of influence peddling. The Legislature, however, was more decisive. They pronounced that “The Tendency of the said Paper is to “Mock Religion, and bring it into Contempt, “That the Holy Scriptures are therein profanely abused, “That the Reverend and Faithful Ministers of the Gospel are injuriously reflected, “On, His Majesty’s Government affronted, and the Peace and good Order of his Majesty’s Subjects of this Province disturbed.” A week later James published his paper including an article by Silence DoGood. He was imprisoned for four weeks. It may be clear that Ben used a pseudonym for practical reasons. It was also a common practice of the times, perhaps for self-preservation. In the end, Ben’s content highlighted the changing mores of Boston and the Puritan’s diminishing sphere of influence. Ben and James never reconciled after James returned from jail. Both, eventually found it necessary to leave Boston in their prime. Ben, soon after, fled south not certain of his destination. Five years later James fled Boston to Rhode Island, following in the footsteps of Puritan reformer, Roger Williams. James wrote under the pen name of Poor Robin. He published almanacs that were distributed in Boston. Poor James, if we might use a second pun, died at the age of thirty-eight. His son, James Jr, became an apprentice for Ben, in Philadelphia. James’ wife, Ann Smith Franklin, continued to publish doing business as “The Widow Franklin.” Our posting on James Franklin may be of interest. He died at the age of thirty-eight. Ben Franklin lived for eighty-four years at a time that male life expectancy was fifty-seven years. Please visit our entertaining blog on Ben Franklin, the maven swimmer. Post Script: Other Ben Franklin pseudonyms;

Bibliography

[i] Mather, Cotton, Essays to Do Good, Andrew Thomson, D. D. Minister of George’s Edingburgh, Glasgow: William White & Co., 1825, 67 references to Do Good, 69 references to good conscience, Google Scholar, https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=F10AAAAAMAAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA49&dq=cotton+mather+%26+Do+Good&ots=B1jNFlYmTv&sig=jVRF0FGmoYSHxyQOYNjSIAz-r7k#v=onepage&q=cotton%20mather%20%26%20Do%20Good&f=false 8. Attributes for the picture of the first letter; http://www.librarycompany.org/bfwriter/writer.htm, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=12440621 Visit our blog on thehistory of the long S as you read early American articles.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Archives

February 2020

|

- Guided Tours

- Self Guide Smartphone Tour

-

Revere Bells Index

- The Stickney Revere Bell Listings of 1976

- Ashby Mass. Revere Bell

- Paul Revere Bell of Beverly

- Revere Bells in Boston >

- California's 2 Paul Revere Bells

- Paul Revere & Son's Bell Westborough Massachusetts

- Falmouth, Massachusetts

- Revere Bell Fredericksburg VA

- Revere Bell Hampton NH

- First Parish Church of Kennebunk

- Revere Bells in Maine

- Revere Bell in Mansfield

- Revere Bell of Michigan

- Revere Salem Mass Bell

- Roxbury First Unitariarn Universalist Church and their Revere Bell

- Revere & Son Bell, Savannah Georgia

- Singapore Revere Bell

- Tuscaloosa Bell >

- Revere Bells Lost in Time

- Revere Bells Washington DC

- Revere Bell in Wakefield, Mass

- Revere Bells Woodstock VT

-

Bostonians

- Edward F Alexander of The Harvard 20th Civil War Regiment

- Polly Baker

- John Wilkes Booth

- The Mad Hatter, Thomas, Boston Corbett who Killed John Wilkes Booth

- Richard-Henry-Dana-Jr

- James Franklin

- Benjamin Harris of Publick Occurrences

- Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr.

- William Lloyd Garrison

- USS Thomas Hudner DDG116

- Edward Hutchinson Robbins Revere

- Amos Lincoln

- King Philip

- Mayor's of Boston

- Mum Bett & Theodore Sedgwick

- James Otis

- Paul Joseph Revere

- Reverend Larkin's Horse

- John Rowe >

- Be Proud to be Called a Lucy Stoner

- Rachel Wall , Pirate

- Paul Revere the Coroner of Boston

- Deborah Sampson

- Who was Mrs. Silence Dogood?

- Dr. Joseph Warren's Dedication

- History Blog

- Lilja's of Natick

-

Collage of Boston

- 4th of July Parade, Bristol RI

- Boston Harbor

- The Customs House

- Forest Hills Cemetery

- Georges Island

- Nonviolent Monument to Peace - Sherborn

- The Battle Road

- Skate bike and scooter park

- Cassin Young & USS Cassin Young

- MIT

- Historic Charles River

- The Roxbury Standpipe on Fort Hill

- John & Abigail Adams National Park

- Boston's Racial History - Ante-Bellum

- New Page

RSS Feed

RSS Feed