- Guided Tours

- Self Guide Smartphone Tour

-

Revere Bells Index

- The Stickney Revere Bell Listings of 1976

- Ashby Mass. Revere Bell

- Paul Revere Bell of Beverly

- Revere Bells in Boston >

- California's 2 Paul Revere Bells

- Paul Revere & Son's Bell Westborough Massachusetts

- Falmouth, Massachusetts

- Revere Bell Fredericksburg VA

- Revere Bell Hampton NH

- First Parish Church of Kennebunk

- Revere Bells in Maine

- Revere Bell in Mansfield

- Revere Bell of Michigan

- Revere Salem Mass Bell

- Roxbury First Unitariarn Universalist Church and their Revere Bell

- Revere & Son Bell, Savannah Georgia

- Singapore Revere Bell

- Tuscaloosa Bell >

- Revere Bells Lost in Time

- Revere Bells Washington DC

- Revere Bell in Wakefield, Mass

- Revere Bells Woodstock VT

-

Bostonians

- Edward F Alexander of The Harvard 20th Civil War Regiment

- Polly Baker

- John Wilkes Booth

- The Mad Hatter, Thomas, Boston Corbett who Killed John Wilkes Booth

- Richard-Henry-Dana-Jr

- James Franklin

- Benjamin Harris of Publick Occurrences

- Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr.

- William Lloyd Garrison

- USS Thomas Hudner DDG116

- Edward Hutchinson Robbins Revere

- Amos Lincoln

- King Philip

- Mayor's of Boston

- Mum Bett & Theodore Sedgwick

- James Otis

- Paul Joseph Revere

- Reverend Larkin's Horse

- John Rowe >

- Be Proud to be Called a Lucy Stoner

- Rachel Wall , Pirate

- Paul Revere the Coroner of Boston

- Deborah Sampson

- Who was Mrs. Silence Dogood?

- Dr. Joseph Warren's Dedication

- History Blog

- Lilja's of Natick

-

Collage of Boston

- 4th of July Parade, Bristol RI

- Boston Harbor

- The Customs House

- Forest Hills Cemetery

- Georges Island

- Nonviolent Monument to Peace - Sherborn

- The Battle Road

- Skate bike and scooter park

- Cassin Young & USS Cassin Young

- MIT

- Historic Charles River

- The Roxbury Standpipe on Fort Hill

- John & Abigail Adams National Park

- Boston's Racial History - Ante-Bellum

- New Page

|

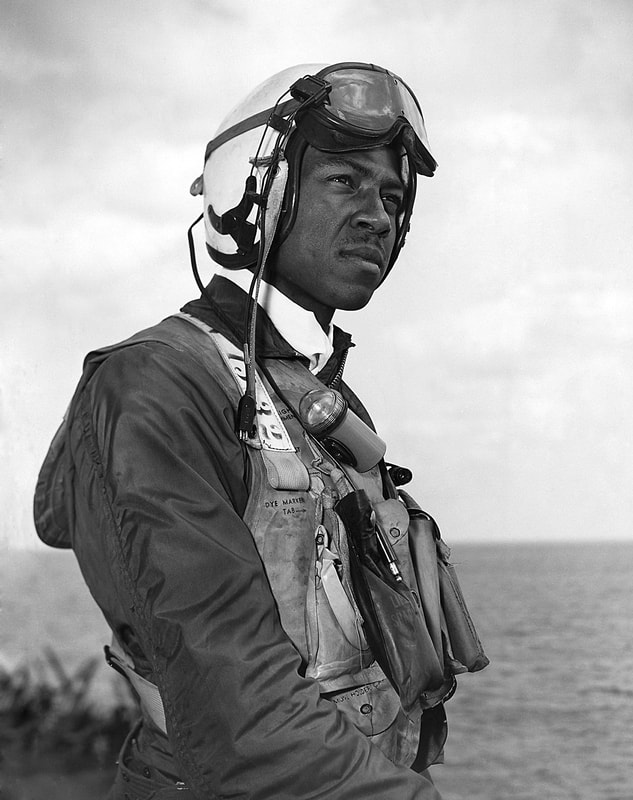

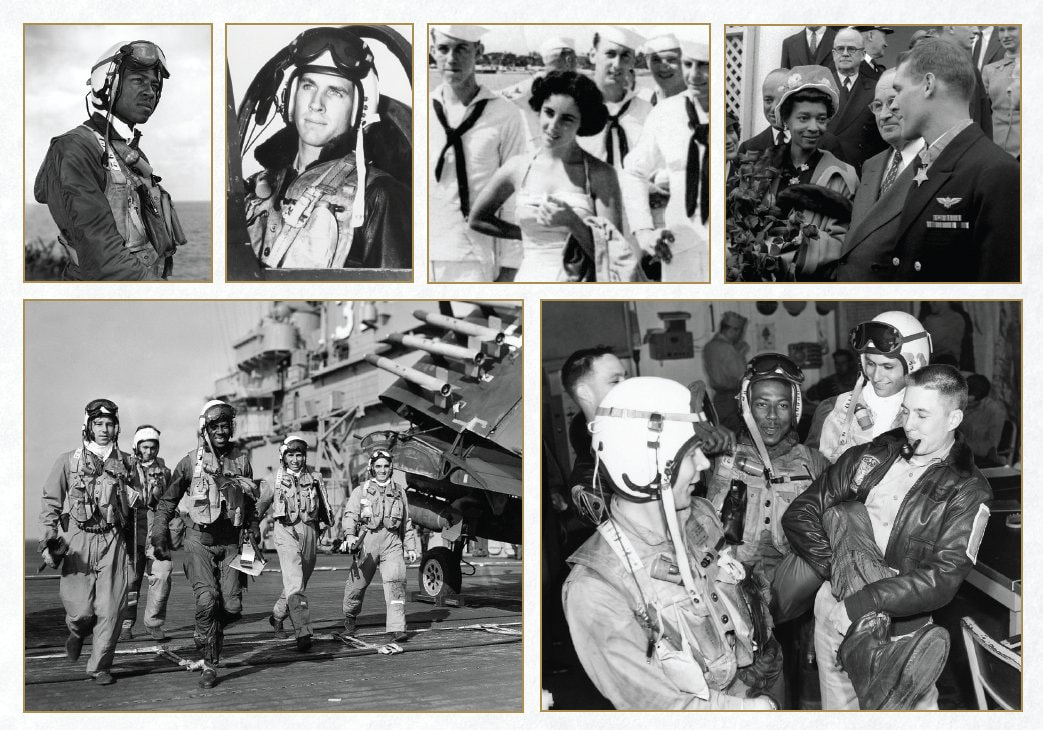

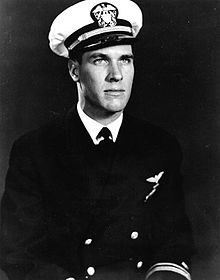

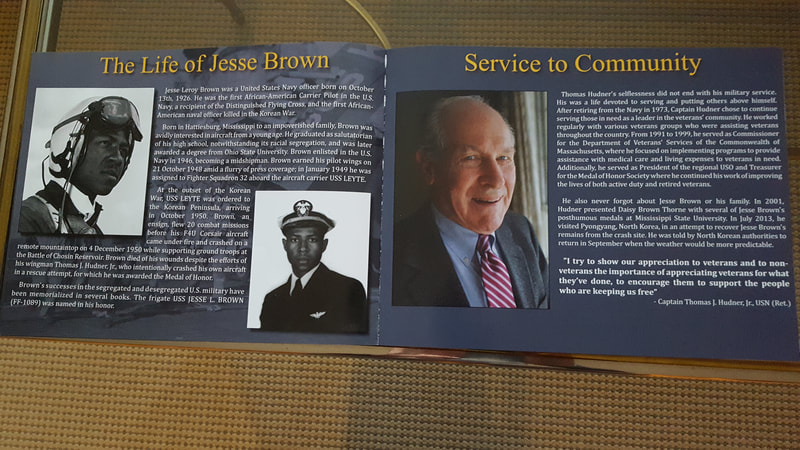

During the first year of the Korean War, Lieutenant Thomas J. Hudner of Fall River, Massachusetts and Ensign Jesse Brown of Hattiesburg, Mississippi were U.S. Navy pilots assigned to the aircraft carrier Leyte. They were wingmen of the VF32nd squadron, flight K from the first day of its formation. Much of their flight training happened in Quonset, Rhode Island. Jesse Brown, his wife Daisy and daughter Pam lived near the base, bringing both of their families in close contact, resulting in a deep friendship.

Tom’s father was a successful owner of a supermarket chain during Fall River’s revival after World War II. Jesse’s father did assembly line work that twice led to lay-offs in Mississippi factory towns. As a result he settled in Lux Mississippi as a sharecropper. The two wing men rose to manhood from completely different levels of society. Yet the two flyers developed similar ethical views of the world. Jesse experienced racism on a daily basis. Tom, experienced America’s subtle form of caste system, trying to be average in a town that was conflicted by budding blue collar prejudice. Both boys fought back against the system in their own way. Jesse read a biography about Jackie Robinson. He never bent to southern prejudice and never raised his hand to strike back. Tom had to defend a weaker friend from the local Portuguese bullies, outnumbered on several occasions and with little support from his Anglo-Saxon friends. By high school graduation the people in each town came to admire the maturity of the two men. The Navy’s path to integration generally mirrored the other military services though out of necessity, for want of sailors it came far sooner than the Army. Early in this nation’s history slaves used the sea to escape and avoid slave hunters. Crispus Attucks, a self- emancipated slave, sailed for twenty years under the name of Michael Johnson, to avoid capture. He was an African American and the very first of five killed during the Boston Massacre. Frederick Douglass escaped slavery in Virginia by borrowing a navy uniform and Seaman's Protection Certificate, documenting that he was a sailor and a citizen of the U.S.[i] At the Battle of Lake Erie, during the War of 1812, African Americans made up one-quarter of the personnel in the nine ships engaged against the British. Early records by the Secretary of the Navy concluded that one-fourth or 29,511 African Americans served in the navy during the Civil War. More recent numbers, based on statistical surveys by Howard University, The Department of the Navy and the National Park Service concluded that eighteen-thousand African Americans served in the Navy.[ii] Most WWII ships at sea were serviced by non-commissioned African Americans. In his non-combatant roll Doris (Dorie) Miller, an African American Navy Launderer, received the Navy Cross, Navy Distinguished Service Medal and Medal of Honor, for his defense of the USS West Virginia during the Japanese surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, December 7, 1941. A few African Americans with WWII experience became naval officers during the Korean War. In contrast, The United States Army abided by a 1792 law that restricted enlistment by African Americans until President Truman’s desegregation order of 1948. The first ever navy aviator to graduate under this new order was Jesse Brown receiving his wings on October 21, 1948. Tom graduated from the United States Naval Academy and Jesse from the Ohio State University. Soon after, Tom Hudner and Jesse Brown were trained to fly as a team at the Quonset Point Naval Air Station in the spring of 1950. Jesse was married, Tom was searching. The Korean War had not begun. Their first port of call was Nice, France, on the Riviera. Elizabeth Taylor, the decade’s hottest starlet, was in Cannes for the film festival. While sun bathing on the beach she was approached by one of Leyte’s marines on liberty. She responded positively and that led to a cohort of more marines engaged in a typical friendly star gazed discussion. She invited them to a 4:00 o’clock tea at her hotel. Tom and Jesse had no knowledge that the Marines from the Leyte had such a lucky moment. Jesse and Tom happened to walked into to the same hotel and sat down for a drink, feeling awkward in such a sophisticated environment. Both flyers were stumbling over a four o’clock refreshment when Elizabeth Taylor walked up to their table. Just a bit of good luck for the flyers. They would meet Elizabeth again that night at the casino, she would visit their ship later in the week. The rules of engagement in Korea were far too well defined. If a flyer was shot down his wingman was not to attempt any rescue that would jeopardize another plane or pilot. The penalty was a court-martial. It appeared that a single rifle shot hit Jesse’s oil line on the fourth day of flying air cover for the Marines surrounded by the Chinese at the Chosin Reservoir. Jesse’s engine was about to fail. He had little choice but to crash land his plane near a mountain top seventeen miles from the nearest Marine base at Hagaru-ri, North Korea. The snow on the mountain hid the moon-like craters and rocks as Jesse crash landed. His plane broke in half trapping his legs under the cockpit. Tom Hudner circled above waiting for Jesse to exit the crashed Corsair. Jesse managed a wave. Minutes later Tom understood that Jesse could not exit the plane on his own. A fire ignited in the fuselage. Tom and Jesse and the four other Corsair pilots circling above, understood the Navy’s position on downed pilots. Nonetheless, Tom Hudner chose to crash land his plane close to Jesse. His plane sustained far less damage but was equally inoperable. As a result a helicopter was dispatched to rescue the pilots. Tom and Jesse were suffering in minus 30 Fahrenheit temperatures. Attempts to remove Jesse from the plane failed. Jesse’s breathing was shallow and erratic. His lips were blue and his skin glazed. With the help of a fireman’s ax and the copter pilot, Jesse could not be freed. As evening set in the helicopter pilot prompted Tom to return with him to base. The copter was not equipped for night flying among mountains that reached above three-thousand five hundred feet and in thin air that reduced the lift of the helicopter blades. Under the trying circumstances Charlie Ward was the only volunteer to come to their aid. As Charlie and Tom walked back to Jesse's plane it was clear that he had perished. Despite numerous efforts they could not free Jesse’s body from the Corsair. Tom returned with the copter to the Leyte a hundred miles from the crash site. He was escorted into the flight room expecting to learn of his court-martial. Instead he was treated as a hero. The next day the ship’s captain, the senior most officer on the carrier, consulted with Tom on Jesse’s remains. Of equal concern was the secret electronic equipment on the Corsair. Tom responded that Jesse would not want another flyer or plane lost in the effort to remove his remains. Tom recalled the hundreds of Chinese in white parkas moving to the crest of the mountain as they made their escape. The captain proceeded to ask if the Leyte should give Jesse a proper burial. Under the circumstances this meant a fly over, recitation of the Lord’s Prayer and the dropping of napalm to seal off the plane and Jesse’s remains. Tom would not accompany the four Corsairs that partook in Jesse’s funeral. On the day of the funeral the pilots noticed that Jesse’s flight clothes had been removed. They gave Jesse the classic fighter send-0ff for a downed pilot behind enemy lines. Three months later the Leyte returned to San Diego for refitting. Elizabeth Taylor was in town and suggested to the Leyte’s captain that she would like to visit with the crew. After some consideration Captain Sisson politely advised Liz that having lost three sailors during this cruise her visit might not be appropriate. In the spring of 1951, Jesse’s last letter to Daisy arrived. It had been mis-directed to a relative. Jesse wrote it the night before his death. The letter is available online. It is four pages of loving thoughts to Daisy and might easily rate as one of the most heart-felt goodbyes. Here is a brief sample; I have to fly tomorrow. But so far as that goes my heart hasn’t been down to earth since the first time you kissed me, and when you love me you “send” it clear out-of-this-world. Listen to or read the full four pages at this location; Devotion: An Epic Story of Heroism, Friendship, and Sacrifice, Adam Makos, Ballantine Books, New York. Also available on CD at most libraries. CD11 Weeks after the Leyte’s return to the United States, Tom received a phone call from the Pentagon and was ordered to the White House to receive the Medal of Honor. Up to this point most publications of Tom and Jesse’s exploits were often slanted by racial preconceptions. Jesse’s wife, Daisy, was asked to attend the White House ceremony. She had not spoken to Tom since the day the Leyte launched for the Mediterranean. The newspaper articles led her to believe that Jesse’s remains were missing. After the ceremony Tom and Daisy met in the White House and for the first time released their emotions. Tom corrected the entire history of that decisive day, explaining to Daisy that a proper funeral took place and the location of the aircraft was documented. He did not hold back the details of the naval funeral. All of this was positively received by Daisy. While Jesse’s last moments were full of gruesome details Daisy was pleased that Jesse did not die alone as implied by many second hand reports. She left with the hope that someday his remains could be properly interred in Arlington National Cemetery. Unfortunately, as of now Jesse’s remains have not been returned to the family. Tom Hudner remained a close friend of Daisy and her daughter Pam until his death. Later in life, Daisy thoroughly briefed Pam on Jesse’s death and provided her with implicit instructions if Jesse’s remains were released by the North Koreans. In 2013 Tom was successful at arranging a trip to North Korea to seek Jesse’s remains. He met with several generals of the North Korean military but returned home with no real assurances. Tom died on November 18, 2017, and to this day Jesse’s remains most certainly are in the hands of the North Koreans. Post Script;

Bibliography

[i] http://www.americaslibrary.gov/aa/douglass/aa_douglass_escape_3.html [ii] https://www.nps.gov/civilwar/soldiers-and-sailors-database.htm Comments are closed.

|

Categories

All

Archives

February 2020

|

- Guided Tours

- Self Guide Smartphone Tour

-

Revere Bells Index

- The Stickney Revere Bell Listings of 1976

- Ashby Mass. Revere Bell

- Paul Revere Bell of Beverly

- Revere Bells in Boston >

- California's 2 Paul Revere Bells

- Paul Revere & Son's Bell Westborough Massachusetts

- Falmouth, Massachusetts

- Revere Bell Fredericksburg VA

- Revere Bell Hampton NH

- First Parish Church of Kennebunk

- Revere Bells in Maine

- Revere Bell in Mansfield

- Revere Bell of Michigan

- Revere Salem Mass Bell

- Roxbury First Unitariarn Universalist Church and their Revere Bell

- Revere & Son Bell, Savannah Georgia

- Singapore Revere Bell

- Tuscaloosa Bell >

- Revere Bells Lost in Time

- Revere Bells Washington DC

- Revere Bell in Wakefield, Mass

- Revere Bells Woodstock VT

-

Bostonians

- Edward F Alexander of The Harvard 20th Civil War Regiment

- Polly Baker

- John Wilkes Booth

- The Mad Hatter, Thomas, Boston Corbett who Killed John Wilkes Booth

- Richard-Henry-Dana-Jr

- James Franklin

- Benjamin Harris of Publick Occurrences

- Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr.

- William Lloyd Garrison

- USS Thomas Hudner DDG116

- Edward Hutchinson Robbins Revere

- Amos Lincoln

- King Philip

- Mayor's of Boston

- Mum Bett & Theodore Sedgwick

- James Otis

- Paul Joseph Revere

- Reverend Larkin's Horse

- John Rowe >

- Be Proud to be Called a Lucy Stoner

- Rachel Wall , Pirate

- Paul Revere the Coroner of Boston

- Deborah Sampson

- Who was Mrs. Silence Dogood?

- Dr. Joseph Warren's Dedication

- History Blog

- Lilja's of Natick

-

Collage of Boston

- 4th of July Parade, Bristol RI

- Boston Harbor

- The Customs House

- Forest Hills Cemetery

- Georges Island

- Nonviolent Monument to Peace - Sherborn

- The Battle Road

- Skate bike and scooter park

- Cassin Young & USS Cassin Young

- MIT

- Historic Charles River

- The Roxbury Standpipe on Fort Hill

- John & Abigail Adams National Park

- Boston's Racial History - Ante-Bellum

- New Page

RSS Feed

RSS Feed