- Guided Tours

- Self Guide Smartphone Tour

-

Revere Bells Index

- The Stickney Revere Bell Listings of 1976

- Ashby Mass. Revere Bell

- Paul Revere Bell of Beverly

- Revere Bells in Boston >

- California's 2 Paul Revere Bells

- Paul Revere & Son's Bell Westborough Massachusetts

- Falmouth, Massachusetts

- Revere Bell Fredericksburg VA

- Revere Bell Hampton NH

- First Parish Church of Kennebunk

- Revere Bells in Maine

- Revere Bell in Mansfield

- Revere Bell of Michigan

- Revere Salem Mass Bell

- Roxbury First Unitariarn Universalist Church and their Revere Bell

- Revere & Son Bell, Savannah Georgia

- Singapore Revere Bell

- Tuscaloosa Bell >

- Revere Bells Lost in Time

- Revere Bells Washington DC

- Revere Bell in Wakefield, Mass

- Revere Bells Woodstock VT

-

Bostonians

- Edward F Alexander of The Harvard 20th Civil War Regiment

- Polly Baker

- John Wilkes Booth

- The Mad Hatter, Thomas, Boston Corbett who Killed John Wilkes Booth

- Richard-Henry-Dana-Jr

- James Franklin

- Benjamin Harris of Publick Occurrences

- Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr.

- William Lloyd Garrison

- USS Thomas Hudner DDG116

- Edward Hutchinson Robbins Revere

- Amos Lincoln

- King Philip

- Mayor's of Boston

- Mum Bett & Theodore Sedgwick

- James Otis

- Paul Joseph Revere

- Reverend Larkin's Horse

- John Rowe >

- Be Proud to be Called a Lucy Stoner

- Rachel Wall , Pirate

- Paul Revere the Coroner of Boston

- Deborah Sampson

- Who was Mrs. Silence Dogood?

- Dr. Joseph Warren's Dedication

- History Blog

- Lilja's of Natick

-

Collage of Boston

- 4th of July Parade, Bristol RI

- Boston Harbor

- The Customs House

- Forest Hills Cemetery

- Georges Island

- Nonviolent Monument to Peace - Sherborn

- The Battle Road

- Skate bike and scooter park

- Cassin Young & USS Cassin Young

- MIT

- Historic Charles River

- The Roxbury Standpipe on Fort Hill

- John & Abigail Adams National Park

- Boston's Racial History - Ante-Bellum

- New Page

|

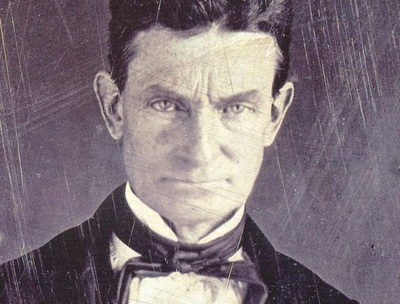

Reverend Theodore Parker of the Secret Six

Theodore Parker was born in Lexington Massachusetts. He was the grandson of Captain John Parker leader of the Lexington Militia that confronted the British Regulars on April 19, 1775, at Lexington Green. Later in the day, Grandad Parker and his militia participated in the rout of the British Army back to Boston. As a minister, Parker was pretty edgy. He rejected all notions of miracles and expressed his certainty that the Bible was historically inaccurate. Transcendentalism moved him further from the New and Old Testament. He chose to break with standard theology. By the time the Civil War began he had a following of seven-thousand parishioners. He suggested to his practitioners that they worship God direct, pray to Him direct; much as the Quakers had in the 17th Century. Since the Quakers were either banished or hung by the Puritans, Parker’s position was bold. We’ll stop here with talk of theology. It is our intent to portray Parker’s relationship with the “Secret Six” that attempted to manage and then fund John Brown’s Raid at Harpers Ferry. Theodore was an Abolitionist that actively resisted the Fugitive Slave Act, embedded in the Compromise of 1850. He demonstrated his commitment to the cause by using his home as a stop on the underground railroad. His most famous visitors were Ellen and William Craft. Ellen was of fair complexion and pretended to be a white woman traveling north with a slave, actually her husband, to avoid detection. Unfortunately, their daring escape was publicized by northern newspapers. Under the new Fugitive Slave Act, they became an obvious target of slave catchers as their former owner placed a large bounty on their heads. Theodore further arranged the Craft’s escape to Canada and on to England. In 1854, Theodore Parker led the charge to free Anthony Burns, held captive at the Federal Courthouse Building in Boston for being a fugitive slave. Slave catchers turned Burns over to federal marshals in Boston. This would be the third Bostonian captured by slave catchers since strengthening of the Fugitive Slave Act. Shadrach Minkins escaped with assistance from abolitionists. Tom Syms escape failed and he was returned to slavery. Reverend Parker was amongst the crowd at Faneuil Hall looking for solutions during and after the trial of Anthony Burns. Thousands were in attendance. By now Abolitionists attempted to pay for Burns freedom. The crowd in and outside the hall started chanting for Parker. He rose and in short order told the crowd that there is “one law. . . and it is in your hands and arms. . . I love peace, but there is a means and there is an end. Liberty is the end”. . . [i] Theodore continued on to call out all of the well know abolitionists in the Hall and questioned their lack of movement. He advised the crowd to meet him at the Court House the next morning at nine o’clock. The crowd could not wait. The call to the Court House arose from the crowd and off they all ran. Well respected abolitionists, lawyers and politicians, joined in with men with clubs and sticks and battered in the Court House door. Soldiers and police slowly retreated up the inner steps towards the jail as the crowd ground to a halt. A shot rang out and James Batchelder, a marshal, lay dead. The crowd fell back as soldiers took charge. To this day the murderer is not known. President Franklin Pierce (raised in New Hampshire) was determined to maintain the law. That night he authorized the use of 200 marines, hired thugs and cannon to move Burns to a waiting military schooner. It took ten days to assemble sufficient force to move Burns down State Street past the symbols of liberty, Faneuil Hall, The Old State House and the Boston Massacre marker. Ironic, if not insane, Burn's owner, Master Suttle, refused $1,200 to free Burns during the Boston trial, but on his return to slavery Suttle sold Burns for $905. Theodore Parker was not deterred by his failure to free Anthony Burns. During the “Bloody Kansas” period of 1854 he financed free Kansas militias, probably well aware that an undeclared civil war had already led to hundreds of deaths. Clearly, Theodore Parker thought outside the box but turned his thoughts into action even if it led to murder. This brings us to his association with John Brown and the Secret Six. Dr. Samuel Gridley Howe of Beacon Hill, Thomas Wentworth Higginson of Worcester, Franklin Sanborn of Concord Massachusetts, Gerrit Smith of New York and George Luther Stearns of Medford, Massachusetts, made up the other members of those to be known as the “Secret Six.”. Over a two-year period, they met with John Brown to discuss financial support for his plan to create a slave revolt. The Parker House, today’s oldest continual hotel, was the scene of their meetings and Brown’s local residence. Initially, The Secret Six engaged with John Brown in support of him in Kansas. Most of the Six were members of various committees to support free slavery causes in Kansas. Support that often led to violence. Soon they specifically knew of John Brown’s plan to attack an arsenal in Virginia to capture the weapons and trigger a slave revolt. The use of violence was confirmed in their letters to each other. [ii] Theodore Parker labeled Brown a “terrorist.” A very interesting term for the period. Combined with Parker’s knowledge of “Captain Brown’s killings in “Bloody Kansas” it seemed conclusive that Parker and each of the Secret Six knew the outcome of financing John Brown. The Secret Six eyes were wide open. A Kansas free militia volunteer under John Brown contacted Franklin Sanborn and demanded money owed him from his service to John Brown. He threatened to expose the plan to attack Harpers Ferry and expose the Secret Six. At this stage in planning, Parker, Sanborn and Smith had serious doubts about John Brown and his plans. After two years of discussion, all six provided funds for John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry. Practically speaking each conceded that if nothing is ventured nothing is gained. Unfortunately, in the year leading to the raid a reporter from New York spent time with John Brown and knew the details of the plan. Upon failure of the raid it was quickly learned of the support provided by the Secret Six. [iii] After Brown was arrested, Parker wrote a public letter, "John Brown's Expedition Reviewed,"[iv] arguing for the right of slaves to kill their masters and defending Brown’s actions.iv Merely a coincidence, Theodore Parker was in Rome at the time of the raid. He was dying of tuberculosis and Italy’s climate was thought to help him recover. He is quoted to have said, as he heard of Brown’s death by hanging; “The road to heaven is as short from the gallows as from the throne.” A convenient position that permits a reverend to balance violence with his ecumenical teachings. He in buried in the English Cemetery in Florence, Italy. Bibliography https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Theodore_Parker Theodore Parker.Commager, Henry Steele, 1902-1998| Beacon Press | [1960]Available at DEAN COLLEGE/Library (BX9869.P3 C65 1960) plus 3 more "Parker, Theodore". Columbia Encyclopedia. [i] Hankins (2004), p.143 ii Renehan, Edward J., Jr. Secret Six: The True Tale of the Men Who Conspired with John Brown. New York City: Crown Publishers, Inc. p.269 [iii] http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/brown/peopleevents/pande06.html [iv] John Brown’s Expedition, A LETTER FROM REV. THEODORE PARKER, AT ROME, BOSTON; PUBLISHED BY THE FRATERNITY 1860, now in the National Archives along with other letters by Parker.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Archives

February 2020

|

- Guided Tours

- Self Guide Smartphone Tour

-

Revere Bells Index

- The Stickney Revere Bell Listings of 1976

- Ashby Mass. Revere Bell

- Paul Revere Bell of Beverly

- Revere Bells in Boston >

- California's 2 Paul Revere Bells

- Paul Revere & Son's Bell Westborough Massachusetts

- Falmouth, Massachusetts

- Revere Bell Fredericksburg VA

- Revere Bell Hampton NH

- First Parish Church of Kennebunk

- Revere Bells in Maine

- Revere Bell in Mansfield

- Revere Bell of Michigan

- Revere Salem Mass Bell

- Roxbury First Unitariarn Universalist Church and their Revere Bell

- Revere & Son Bell, Savannah Georgia

- Singapore Revere Bell

- Tuscaloosa Bell >

- Revere Bells Lost in Time

- Revere Bells Washington DC

- Revere Bell in Wakefield, Mass

- Revere Bells Woodstock VT

-

Bostonians

- Edward F Alexander of The Harvard 20th Civil War Regiment

- Polly Baker

- John Wilkes Booth

- The Mad Hatter, Thomas, Boston Corbett who Killed John Wilkes Booth

- Richard-Henry-Dana-Jr

- James Franklin

- Benjamin Harris of Publick Occurrences

- Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr.

- William Lloyd Garrison

- USS Thomas Hudner DDG116

- Edward Hutchinson Robbins Revere

- Amos Lincoln

- King Philip

- Mayor's of Boston

- Mum Bett & Theodore Sedgwick

- James Otis

- Paul Joseph Revere

- Reverend Larkin's Horse

- John Rowe >

- Be Proud to be Called a Lucy Stoner

- Rachel Wall , Pirate

- Paul Revere the Coroner of Boston

- Deborah Sampson

- Who was Mrs. Silence Dogood?

- Dr. Joseph Warren's Dedication

- History Blog

- Lilja's of Natick

-

Collage of Boston

- 4th of July Parade, Bristol RI

- Boston Harbor

- The Customs House

- Forest Hills Cemetery

- Georges Island

- Nonviolent Monument to Peace - Sherborn

- The Battle Road

- Skate bike and scooter park

- Cassin Young & USS Cassin Young

- MIT

- Historic Charles River

- The Roxbury Standpipe on Fort Hill

- John & Abigail Adams National Park

- Boston's Racial History - Ante-Bellum

- New Page

RSS Feed

RSS Feed