- Guided Tours

- Self Guide Smartphone Tour

-

Revere Bells Index

- The Stickney Revere Bell Listings of 1976

- Ashby Mass. Revere Bell

- Paul Revere Bell of Beverly

- Revere Bells in Boston >

- California's 2 Paul Revere Bells

- Paul Revere & Son's Bell Westborough Massachusetts

- Falmouth, Massachusetts

- Revere Bell Fredericksburg VA

- Revere Bell Hampton NH

- First Parish Church of Kennebunk

- Revere Bells in Maine

- Revere Bell in Mansfield

- Revere Bell of Michigan

- Revere Salem Mass Bell

- Roxbury First Unitariarn Universalist Church and their Revere Bell

- Revere & Son Bell, Savannah Georgia

- Singapore Revere Bell

- Tuscaloosa Bell >

- Revere Bells Lost in Time

- Revere Bells Washington DC

- Revere Bell in Wakefield, Mass

- Revere Bells Woodstock VT

-

Bostonians

- Edward F Alexander of The Harvard 20th Civil War Regiment

- Polly Baker

- John Wilkes Booth

- The Mad Hatter, Thomas, Boston Corbett who Killed John Wilkes Booth

- Richard-Henry-Dana-Jr

- James Franklin

- Benjamin Harris of Publick Occurrences

- Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr.

- William Lloyd Garrison

- USS Thomas Hudner DDG116

- Edward Hutchinson Robbins Revere

- Amos Lincoln

- King Philip

- Mayor's of Boston

- Mum Bett & Theodore Sedgwick

- James Otis

- Paul Joseph Revere

- Reverend Larkin's Horse

- John Rowe >

- Be Proud to be Called a Lucy Stoner

- Rachel Wall , Pirate

- Paul Revere the Coroner of Boston

- Deborah Sampson

- Who was Mrs. Silence Dogood?

- Dr. Joseph Warren's Dedication

- History Blog

- Lilja's of Natick

-

Collage of Boston

- 4th of July Parade, Bristol RI

- Boston Harbor

- The Customs House

- Forest Hills Cemetery

- Georges Island

- Nonviolent Monument to Peace - Sherborn

- The Battle Road

- Skate bike and scooter park

- Cassin Young & USS Cassin Young

- MIT

- Historic Charles River

- The Roxbury Standpipe on Fort Hill

- John & Abigail Adams National Park

- Boston's Racial History - Ante-Bellum

- New Page

What did the Best Swimmer in Colonial America, Ben Franklin and Paul Revere have in Common?10/28/2016 Daily, I turn to Ben Franklin’s autobiography to get away from the more detailed military, legal and political history of Colonial Boston. It is a delightful surrey through the life and times of an adventuresome boy quickly becoming a man of the world.

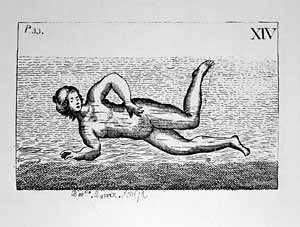

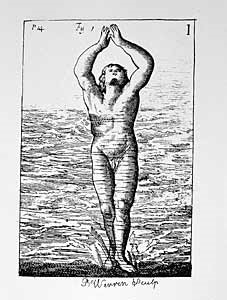

On page forty-seven[i], Ben highlights his attempt to teach his younger friends the sport of swimming. His friends delighted in his ability to maneuver through the water and do tricks below and above the water. Hardly the rotund image we have of Ben cavorting through Paris with the gout as his walking companion. Ben may well have used the rivers and oceans to bathe but it would appear he loved the sport of it above bathing’s other values. In Boston Ben had early thoughts of being a sailor. As most accounts suggest, sailors were not required to swim. He loved the sport of swimming but may well have seen its survival benefits as a sailor. Yet Ben, the perennial inventor, was attributed with improvising hand flippers, from an artist paint pallet, to increase his speed in the water. This is just Ben being Ben. At the age of twenty-one he swam three and a half miles in the Thames from Chelsea to Blackfriars, London. It appears that there were numerous witnesses. As a parity check, I swim one-half mile in 21 minutes. This might suggest that Ben swam two or three hours, apparently without rest, being acrobatic most of the way, according to independent accounts. Most swimmers today would be proud of this accomplishment. Always the entrepreneur, Ben earned money in London teaching children of wealthy families to swim. He contemplated opening a swimming school but tired of London and returned to Philadelphia. Europeans used some unusual methods to enter the water to swim. The upper class often wheeled make-shift changing rooms down to the ocean or lake and entered through doors that opened out to the ocean or river, permitting them to quickly duck below the water line. The middle class often walked into the water covering their bathing attire with a cotton robe that was discarded once ankle deep. To my surprise several east coast Indian and Caribbean tribes had perfected the crawl stroke while most Europeans knew only the breast stroke. Many African American slaves used the crawl stroke to escape slave ships approaching the shore line. Sorry Australia, the crawl did not originate with you. Historically, swimming seemed pervasive from continent to continent and from the Greek period through the 19th Century. Modesty may well have depressed the sport of swimming among the Puritan Bostonians. Ben was born Puritan. His father appeared to be Godly.[ii] Yet nudity did not seem to halt Ben from his many public swims. So it is a wonder to me that so many Bostonians drowned in the period from 1796 to 1801. I point to this period having followed Paul Revere through his assignment as one of the Coroners of Boston. Paul conducted full inquests sitting thirteen citizens on each of the forty-six inquest juries. Eighteen adults drowned in the course of Paul’s five-year assignment and he was not the only coroner in Boston at this time, so deaths by drowning may have been higher. The population of Boston was about 15,000 during Paul’s time as coroner. Yet, of the forty-six inquests, drowning was the cause of death in thirty-five percent of all the sudden deaths. Today, The Center for Disease Control says that ten people drown each day in America. Yet they estimate only fifty-percent of Americans really know how to swim to save their life. Certainly, this deserves further study by the CDC or the World Health Organization as it is a world-wide issue. As for Walkbostonhistory.com, please follow us on Twitter at @walkbostonhist. We are completing our article exploring Paul Revere’s work as a coroner of Boston, including the eighteen deaths by drowning and other causes. It should be a look at Colonial Boston from a very unique perspective. Here’s an advance look at our Paul Revere tour. http://www.walkbostonhistory.com/walk-the-18th-century-with-paul-revere.html Famous Remarks Around the World on Swimming[iii] Witness John Locke, who, in Some Thoughts concerning Education, published in 1693, said every child should be taught to swim when old enough to learn and had someone to teach him. He wrote: ’Tis that saves many a man’s life: and the Romans thought it so necessary that they ranked it with letters, and was the common phrase to mark one ill educated and good for nothing that he had neither learned to read nor to swim. . . . But besides the gaining a skill which may serve him at need, the advantages to health, by often bathing in cold water during the heat of summer, are so many that I think nothing need to be said to encourage it, provided this one caution be used that he never go into the water when exercise has at all warmed him or left any emotion in his blood or pulse. Like Locke, Benjamin Franklin thought every youth should learn to swim. In an undated letter written before 1769, Franklin said he believed they would on many occurrences, be the safer for having that skill, and on many more the happier, as freer from painful apprehensions of danger, to say nothing of the enjoyment in so delightful and wholesome an exercise. Soldiers particularly should, methinks, all be taught to swim; it might be of frequent use either in surprising an enemy, or saving themselves. And if I had now boys to educate, I should prefer those schools (other things being equal) where an opportunity was afforded for acquiring so advantageous an art, which once learnt is never forgotten. The Romans swam for recreation and for warfighting. Julius Caesar was noted for his swimming. Nicholas Orme wrote in Early British Swimming, 55 b.c.-a.d. 1719: The writings of Rome in the classical era: history and biography, letters and poetry, include numerous mentions of swimming. . . . Swimming had high status as a healthy, manly and useful activity; it was thought of as essentially and traditionally Roman, and was traced back to the legendary hero Horatius Cocles who had swum the Tiber memorably after defending the bridge against the Etruscans. Francis Place’s autobiography says that during the summer boys often swam in the River Thames. He remembered that when he was about eleven, “I saw boys not older than myself swim across the Thames at Millbank at about half tide.” By 1743, recreational swimming was popular enough that the Peerless Pool was described as “an elegant pleasure bath,” 170 feet by 100 feet, with a smooth gravel bottom. It was accessed by several flights of steps . . . adjoining to which are boxes and arbours for dressing and undressing, some of them open, some enclosed. On the south side is a neat arcade under which is a looking glass over a marble slab, and a small collection of books for the entertainment of the subscribers. . . . here is also a cold bath the largest in England. . . . The free use of the place is purchased by the easy subscription of one guinea per annum. In 1741 another swimming pool was advertised in a London newspaper. It was near the London Infirmary and offered a “swimming bath which is convenient for swimming or for gentlemen to learn to swim in.” Instructors were available to teach gentlemen to swim. References to people swimming in colonial Virginia usually instance occasions of necessity, not pleasure. Nicholas Cresswell, for example, said that during a trip on the Ohio in 1775 one of the canoes drifted across the river and “one of the Company swam across the River and brought her over.” But the year before, when he was in Barbados, Cresswell wrote, “Early this morning Bathed in the Sea, which is very refreshing in this hot Climate.” As Franklin said, some enjoyed swimming for recreation. The number of coroner’s inquests conducted in colonial Virginia on the bodies of boys and young men who drowned while swimming suggests the practice was widespread. When George Washington was nineteen, someone stole his clothes while he was swimming in the Rappahannock River. This being Sunday, we were glad to rest from our labors; and, to help restore our vigor, several of us plunged into the river, notwithstanding it was a frosty morning. One of our Indians went in along with us and taught us their way of swimming. They strike not out both hands together but alternately one after another, whereby they are able to swim both farther and faster than we do. Some Native Americans were adept, which drew comment from settlers in North and South America. The stroke the Indians employed as described by Byrd seems to be a crawl or perhaps a dog paddle. Byrd was evidently unfamiliar with that style, having practiced what appears to be a breaststroke. Of course, a crawl is faster than a breaststroke. Tribes inhabiting areas without large rivers were apparently ignorant of the skill. In 1792, John Rogers told Governor Henry Lee why Choctaws lost so many men in a war with the Creeks at the time of the American Revolution. “The Choctaws laboured under a disadvantage which lost them many men,” he wrote, “which was the want of the art of swimming.” The Choctaws “were frequently overtaken on their retreat by superior numbers of Creeks, and cut to pieces upon the banks of large Rivers, or forced in & drowned.” A hundred years later, in 1696, The Art of Swimming was published in France. Three years later it was translated into English. The book proved popular, and a third English edition was published in 1789. The author, Melchisédech Thévenot, wrote that because a person is “near the like weight with water,” swimming is easy “insomuch that lying on his back without motion, and holding in his breath he cannot sink.” Thévenot details the mechanics of stroking: [i] The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin, “The Private Life of the Late Benjamin Franklin LL,D. published 1791 in French, 1793 in English [ii] Godly was the name New England Puritans called themselves. [iii] http://www.history.org/Foundation/journal/Winter01-02/Swim.cfm

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Archives

February 2020

|

- Guided Tours

- Self Guide Smartphone Tour

-

Revere Bells Index

- The Stickney Revere Bell Listings of 1976

- Ashby Mass. Revere Bell

- Paul Revere Bell of Beverly

- Revere Bells in Boston >

- California's 2 Paul Revere Bells

- Paul Revere & Son's Bell Westborough Massachusetts

- Falmouth, Massachusetts

- Revere Bell Fredericksburg VA

- Revere Bell Hampton NH

- First Parish Church of Kennebunk

- Revere Bells in Maine

- Revere Bell in Mansfield

- Revere Bell of Michigan

- Revere Salem Mass Bell

- Roxbury First Unitariarn Universalist Church and their Revere Bell

- Revere & Son Bell, Savannah Georgia

- Singapore Revere Bell

- Tuscaloosa Bell >

- Revere Bells Lost in Time

- Revere Bells Washington DC

- Revere Bell in Wakefield, Mass

- Revere Bells Woodstock VT

-

Bostonians

- Edward F Alexander of The Harvard 20th Civil War Regiment

- Polly Baker

- John Wilkes Booth

- The Mad Hatter, Thomas, Boston Corbett who Killed John Wilkes Booth

- Richard-Henry-Dana-Jr

- James Franklin

- Benjamin Harris of Publick Occurrences

- Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr.

- William Lloyd Garrison

- USS Thomas Hudner DDG116

- Edward Hutchinson Robbins Revere

- Amos Lincoln

- King Philip

- Mayor's of Boston

- Mum Bett & Theodore Sedgwick

- James Otis

- Paul Joseph Revere

- Reverend Larkin's Horse

- John Rowe >

- Be Proud to be Called a Lucy Stoner

- Rachel Wall , Pirate

- Paul Revere the Coroner of Boston

- Deborah Sampson

- Who was Mrs. Silence Dogood?

- Dr. Joseph Warren's Dedication

- History Blog

- Lilja's of Natick

-

Collage of Boston

- 4th of July Parade, Bristol RI

- Boston Harbor

- The Customs House

- Forest Hills Cemetery

- Georges Island

- Nonviolent Monument to Peace - Sherborn

- The Battle Road

- Skate bike and scooter park

- Cassin Young & USS Cassin Young

- MIT

- Historic Charles River

- The Roxbury Standpipe on Fort Hill

- John & Abigail Adams National Park

- Boston's Racial History - Ante-Bellum

- New Page

RSS Feed

RSS Feed